Deep Dive: Intel Corp (INTC)

I sold TSM 0.00%↑ early January 2026 and bought INTC 0.00%↑. If you are underwriting both companies in a model, and are purely focused on fundamentals - you’d regard this trade as extremely stupid. However, as I was thinking ways to hedge the current AI heavy equity portfolio I realized that the only true hedge to China/Taiwan escalation is owning Intel, now backstopped by Trump administration.

Intel is emerging from one of its darkest cycles into a politically supercharged turnaround narrative. The stock has more than doubled over the past year (up 106% year-on-year as of Jan 23, 2026[1]) amid a collapsing PC market bottom, early signs of data center recovery, and an unprecedented U.S. government stake in the company.

Intel now sits at the nexus of post-downturn demand resurgence and geopolitical urgency: it’s the only advanced logic fab in the Western hemisphere, positioned as a hedge against a fragile Taiwan supply chain. The market’s dominant belief is that “New Intel” – under CEO Lip-Bu Tan since 2025 – will reclaim process technology leadership and supply security, riding the AI compute wave.

Intel’s stock is telling a very different story than its income statement. Investors have bid up Intel as a national champion and AI beneficiary, pricing in a future that management has yet to deliver in profit. The company’s market cap (~$225 billion at $45/share[2]) now anticipates a successful turnaround, even as trailing margins hover near breakeven and free cash flow remains in the red.

This creates a tension: Is Intel a credible secular revival – the right side of a once-in-a-generation inflection – or a capital-intensive hope trade that’s outrunning its underlying economics? The answer lies in whether Intel’s aggressive bets on leading-edge manufacturing and foundry-for-hire can translate into tangible competitive and financial gains before the narrative wears thin.

What They Do

Intel designs and manufactures microprocessors and related chips, primarily for personal computers and servers.

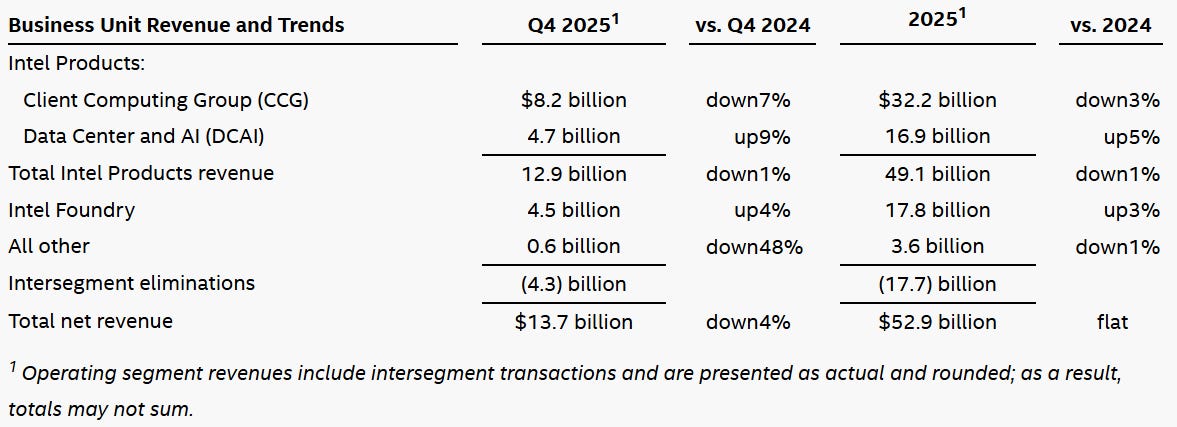

Its Client Computing Group (CCG) sells PC CPUs (the familiar Core processors for laptops and desktops), which drove $32.2 billion of revenue in 2025 (61% of total)[3][4].

Its Data Center and AI (DCAI) group provides Xeon server CPUs and adjacent accelerators for cloud providers and enterprises, contributing $16.9 billion in 2025 (32% of revenue)[5][6].

These two segments generate the bulk of Intel’s economic value, historically with data center chips commanding the highest margins.

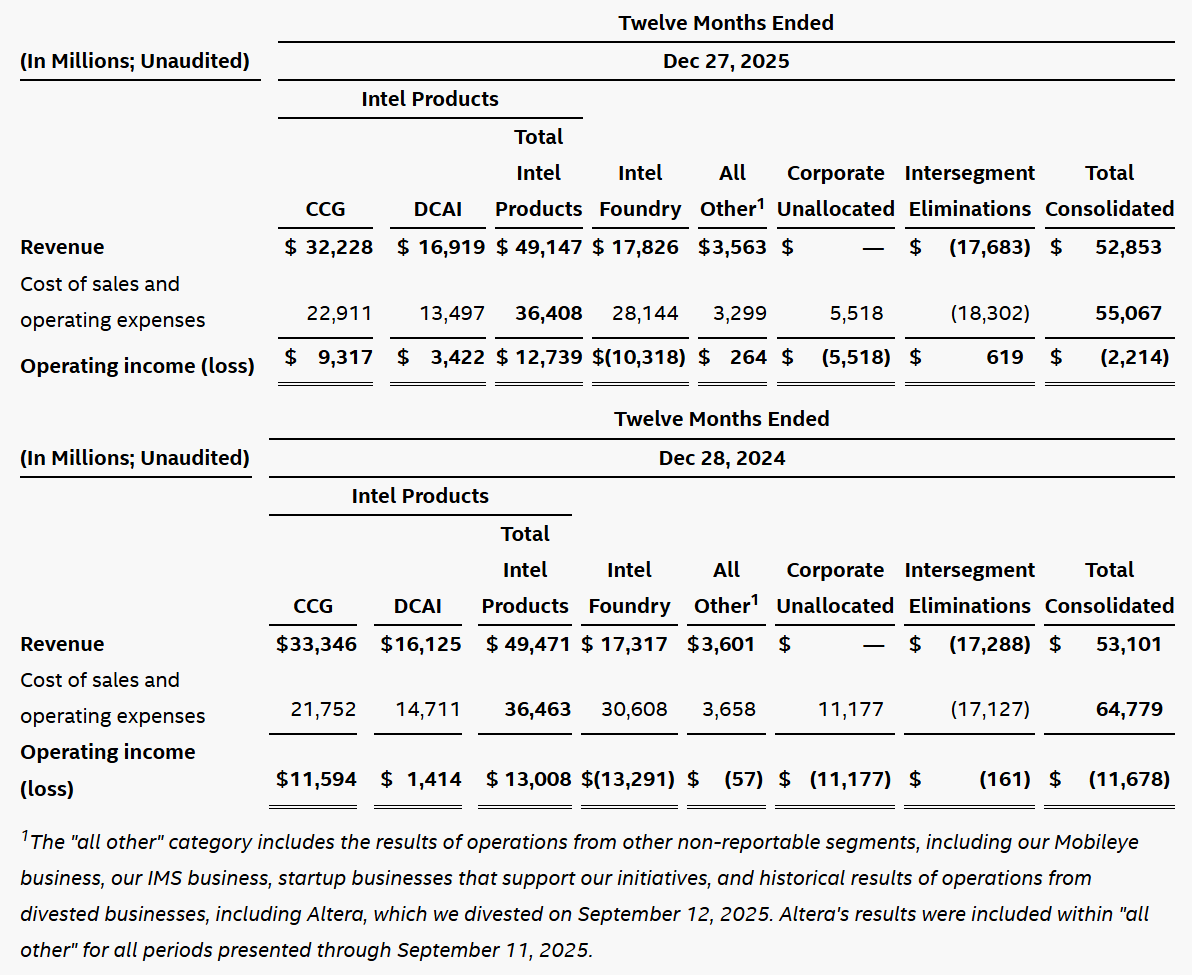

Intel is also building Foundry Services, opening its factories to make chips for external customers. While foundry revenue is currently reported at $17.8 billion (which includes sales of wafers and packaging, largely to other Intel groups)[7][8], this business still operates at a steep loss.

In plain terms, Intel is a vertically integrated chipmaker – it designs its own x86 processors and manufactures them in-house – now also trying to become a contract manufacturer for others. Ancillary businesses (like Mobileye autonomous driving, and recently-divested FPGA units) are relatively small. The core driver is selling compute chips, and the lion’s share of profits (when Intel has them) comes from server and high-end PC processors where it historically enjoyed near-monopoly pricing power.

The Thesis

Intel is attempting to reinvent itself from a legacy PC-centric OEM into a next-generation semiconductor platform company. Management’s vision is for Intel to be both a leading product company (delivering CPUs, GPUs, and custom AI silicon across client and data center) and a leading foundry (manufacturing the chips of other industry players). In effect, Intel wants to evolve from a margin-rich but insular x86 franchise into a broader ecosystem linchpin – akin to TSMC in manufacturing and still Nvidia/AMD in chip design.

This identity hinges on Intel achieving scarcity value at the cutting edge: if it can develop process technology equal to or better than TSMC’s, its U.S.-based fabs become a scarce strategic asset, allowing it to earn scarcity rents (premium pricing and government support) rather than just “clearing the market” at commodity prices[9][10].

In CEO Lip-Bu Tan’s words, the goal is to build a “new Intel” focused on execution and engineering excellence[11] – effectively shedding the complacency of the past decade. The company is trying to position itself as the indispensable American semiconductor champion, supplying both its own products and others’, rather than a fading incumbent defending PC market share. This is a bold identity shift: from aging monopolist to agile hybrid foundry, from volume-driven supplier to val ue-driven platform at the heart of the AI era.

The Trade

The investment thesis here centers on mispriced transformation. Intel’s current valuation reflects skepticism mixed with hope – the stock trades ~45× forward earnings[2] because near-term EPS is depressed, yet at ~4.3× sales it isn’t pricing the kind of hyper-growth that pure-play foundries or AI chip designers get. The opportunity, if one is bullish, is that the market still underestimates Intel’s turnaround potential: that a company left for dead in 2022 can double gross margins and regain technology leadership, yielding significant operating leverage and multiple expansion.

Conversely, the risk is that optimism is too far ahead of reality – that Intel’s recent rally (over +100% in a year) has already priced in a best-case scenario of manufacturing success and share regain that may not fully materialize[12].

The why now is clear: Intel has just begun shipping chips on its new 18A process node and secured heavy U.S. government backing, marking 2025 as the turning point when evidence of progress finally emerged[10][13]. The stock’s surge anticipates a multiyear inflection starting now. Our task is to decide if today’s price leaves sufficient mispricing gap – i.e. whether Intel’s fundamentals can outpace the already-shifting narrative from here.

The single variable that will decide Intel’s fate is leading-edge process execution – specifically, the success of the Intel 18A node and its ability to attract large external customers. Everything flows from this fulcrum. If Intel’s 18A process (roughly equivalent to TSMC’s 2nm generation) delivers competitive transistor performance at volume yields, Intel will not only power its own next-gen CPUs but also prove itself as a credible foundry for others. This in turn would drive a sustained recovery in high-margin server CPUs (since process parity stops AMD’s advance) and give foundry customers confidence to port their designs to Intel fabs. In short, 18A yield ramp and customer traction is the make-or-break. One could argue the fulcrum is gross margin, or free cash flow, but those are second-order outcomes – gross margin will rise if 18A succeeds (and sink if it doesn’t, due to underutilized capacity). Even geopolitical tailwinds and government deals ultimately depend on Intel proving it can manufacture at the leading edge. Thus, the crux is whether Intel can execute technologically after years of missteps. A clear marker will be if Intel can hit its 2026 goal of process parity with TSMC and start moving ahead by 2027 (when 18A’s successor, 14A, is expected)[15][16]. That will determine if Intel becomes the go-to foundry alongside TSMC or remains an also-ran with expensive empty fabs.

If Intel wins on that fulcrum, the upside mechanics are powerful and potentially self-reinforcing. Success on 18A would mean Intel’s 2026–2027 product lineup (Panther Lake PC CPUs, Clearwater Forest server CPUs, etc.) can reclaim performance leadership, driving higher ASPs and unit share against AMD[17][18].

External customers – who are desperate for a second source beyond TSMC – would likely sign sizable foundry contracts (we are already seeing early indications: reports suggest Intel has landed Apple’s low-end Mac chip business on 18A for 2027). This would fill Intel’s fabs, improving utilization and gross margin dramatically from the current ~35% into the 40s% and higher[21]. Higher margins and returning growth would then feed a reflexive loop: improving cash flow to fund further node R&D, which secures future leadership, and so on. In an upside case, one can imagine Intel’s earnings power in 3-4 years easily exceeding $3–4 per share (vs. essentially $0 in 2025), which at even a market-multiple could justify a stock well above $60. Moreover, if Intel truly reestablishes itself as a technology leader, the market might accord it a higher multiple more akin to a foundry or a fabless peer, yielding further upside.

There is also a strategic kicker: Intel’s unique position as the only advanced fab outside Asia could command scarcity premium valuation if global investors seek a geopolitical hedge in semis.

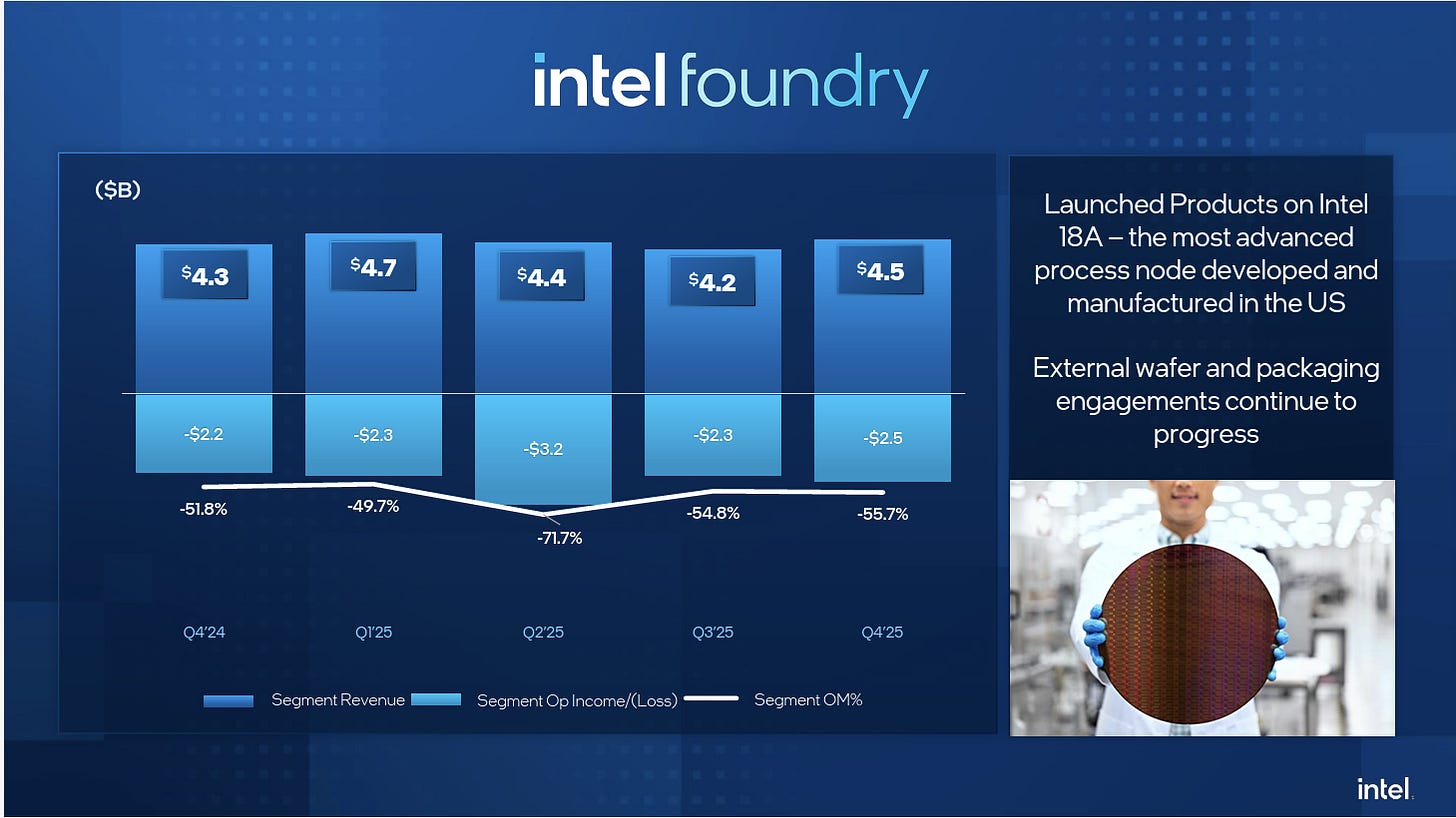

The downside, however, is that Intel remains what it has been – a capital intensive story trading ahead of fundamentals. In a bear scenario, 18A could suffer yield delays or cost overruns (not uncommon in Intel’s past). That would mean Intel’s much-touted products slip in performance or timing, leading it to continue losing share to AMD and Nvidia in key workloads. External foundry customers would walk away if Intel can’t deliver competitive chips on schedule – recall that Intel lost credibility with previous nodes, and any stumble now would cement skepticism. The financial mechanics of downside are stark: Intel is currently pouring >30% of revenue into capex and R&D (over $18 billion in 2025 R&D, and gross capital expenditures on the order of $20 billion[22][23]). If those investments don’t yield leadership, they become sunk costs that erode returns. Underutilized fab capacity would force Intel to “clear at the margin,” cutting chip prices just to cover fixed costs. We’ve already seen glimpses of this – Intel’s foundry division lost an astonishing $2.5 billion in Q4 alone on $4.5 billion revenue (a –56% operating margin)[24].

In a failure scenario, such losses could accumulate and strain the balance sheet, especially as debt is high (>$44 billion) and interest rates are up. The stock, in that case, could de-rate sharply back toward pure-value territory (think price/sales of 2x or less). Put bluntly, the downside is that Intel becomes a value trap: a lot of shiny new fabs, but not enough profit to show for it – reminiscent of late 1990s chip glut dynamics, this time with Intel playing catch-up instead of leading.

Financials

For the time being, I don’t really care about INTC 0.00%↑ financials… Nevertheless:

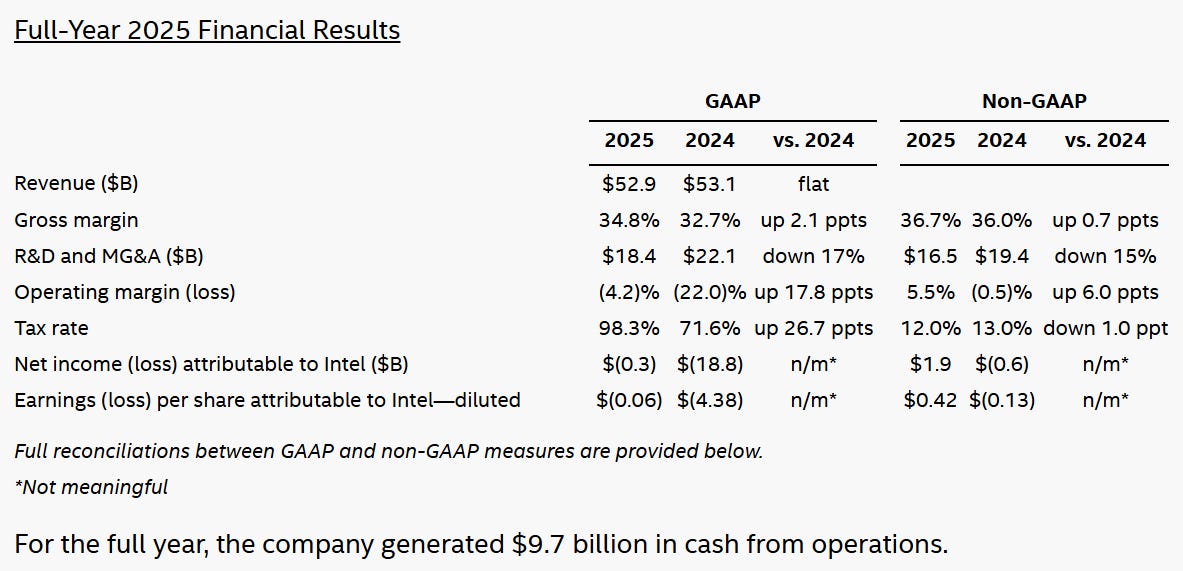

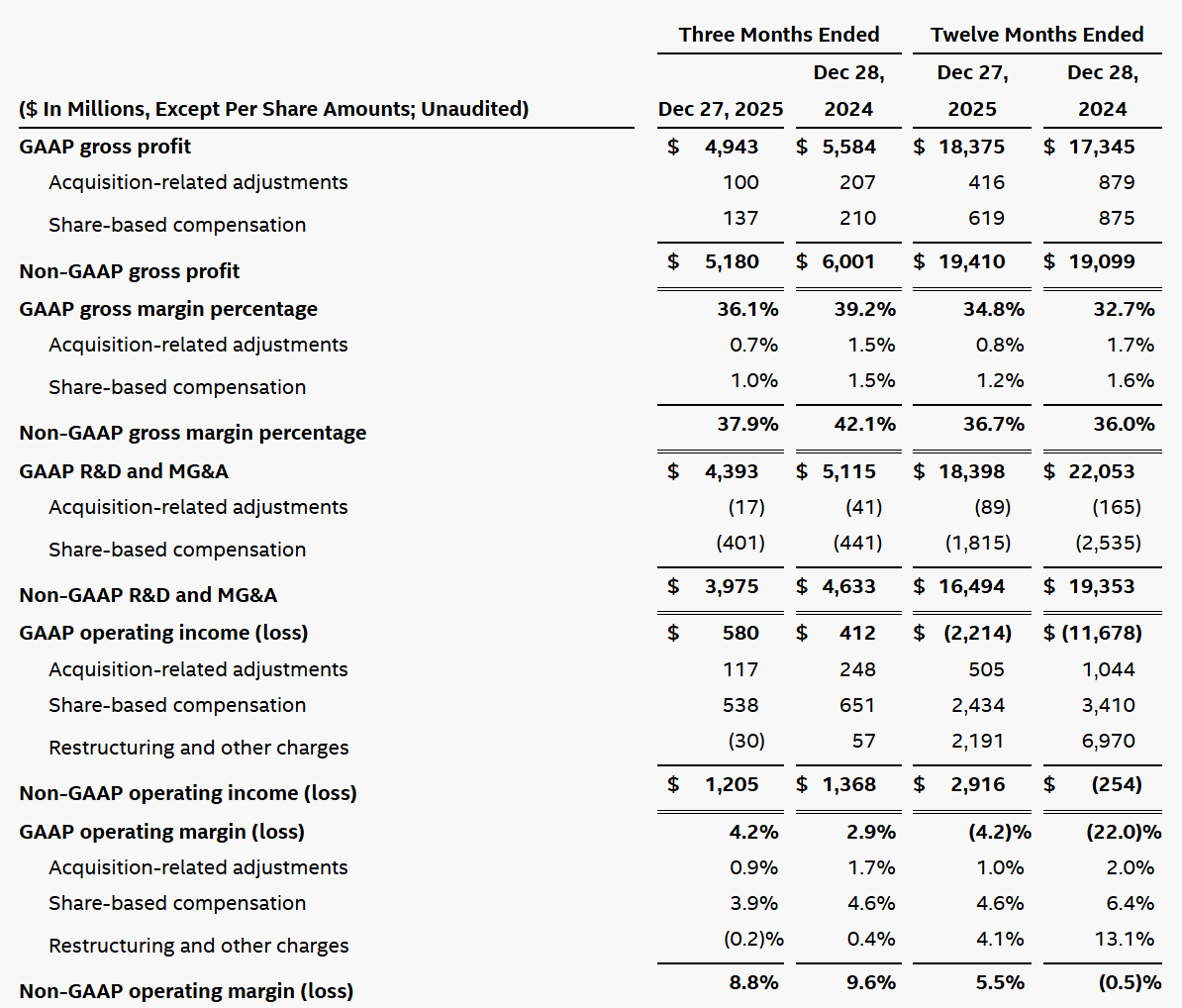

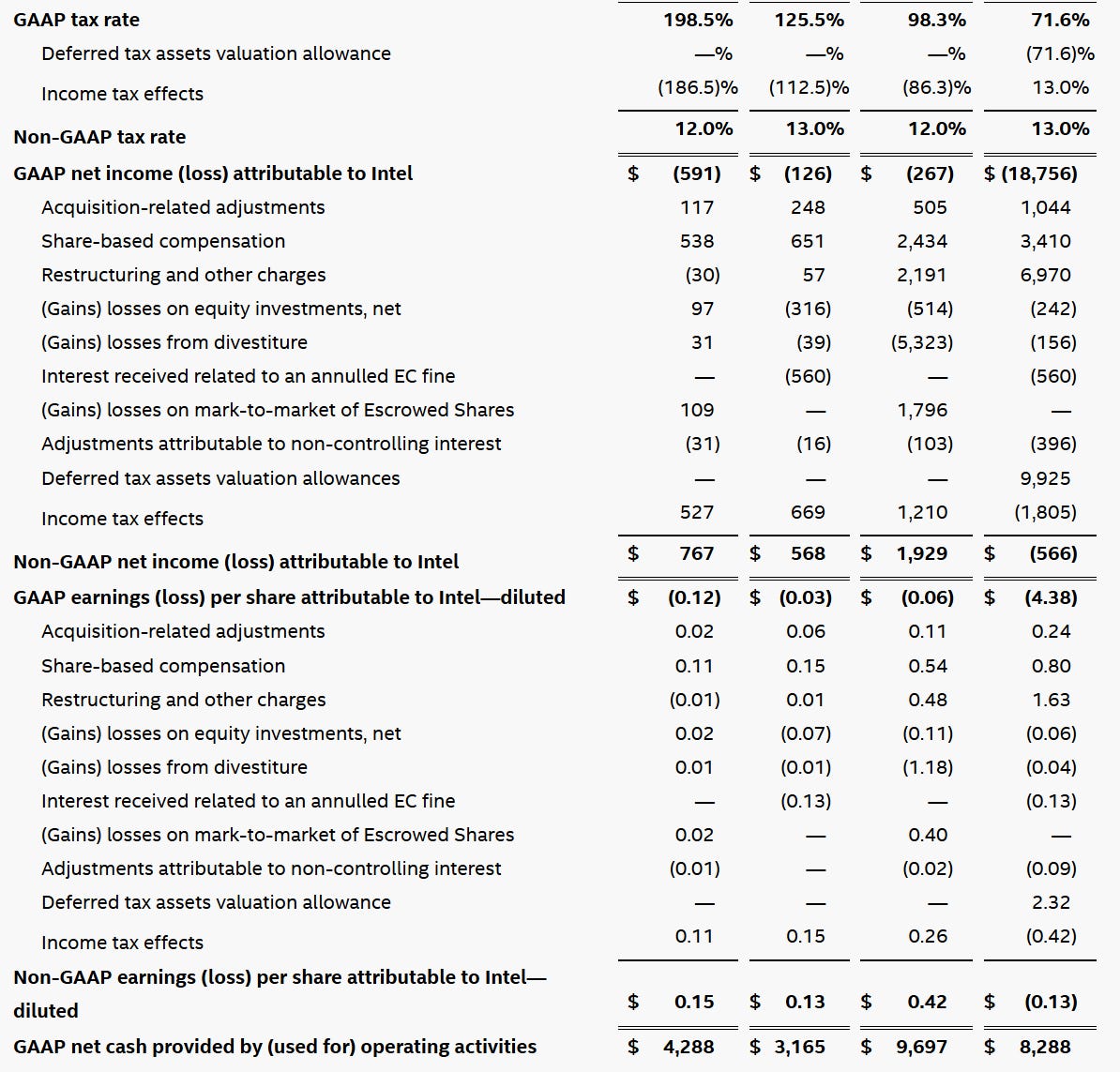

Intel’s latest financials underscore a business that is just emerging from a downturn and heavy restructuring. In 2025, Intel generated $52.9 billion in revenue (flat vs 2024)[26], marking a stabilization after prior steep declines.

Gross margin was 34.8% (GAAP) for 2025 (36.7% on a non-GAAP basis)[27] – depressed by underutilized factories and start-up costs on new process nodes, and far below Intel’s historical ~55–60% gross margins. Operating income was roughly breakeven: a $(0.3) billion GAAP net loss for 2025[28], though on an adjusted basis Intel eked out $1.9 billion in net profit[29].

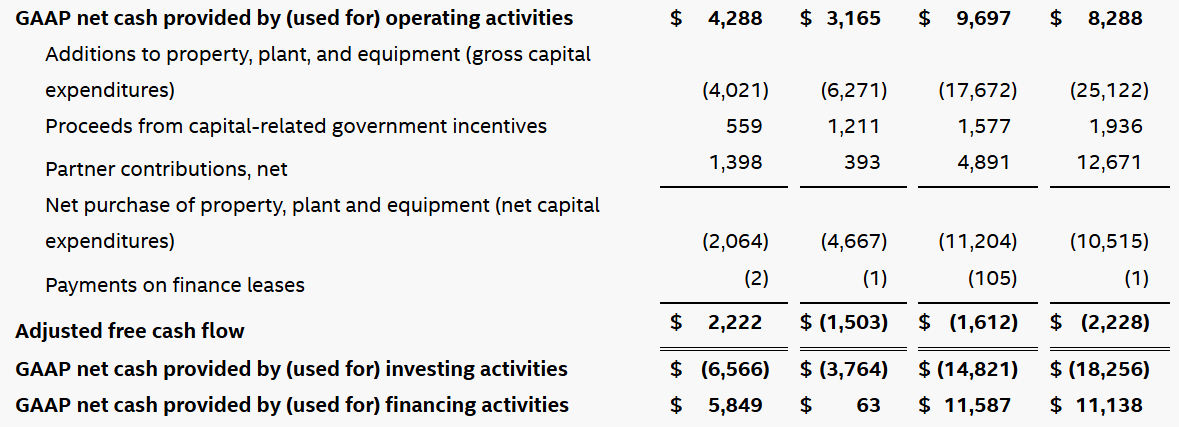

This is a dramatic improvement from 2024’s losses (Intel lost almost $19 billion GAAP in 2024 amid inventory write-downs and impairments)[30], but it shows how thin current profitability is. Free cash flow remains negative – Intel reported –$1.6 billion adjusted free cash flow for 2025[31], its third consecutive year of cash burn.

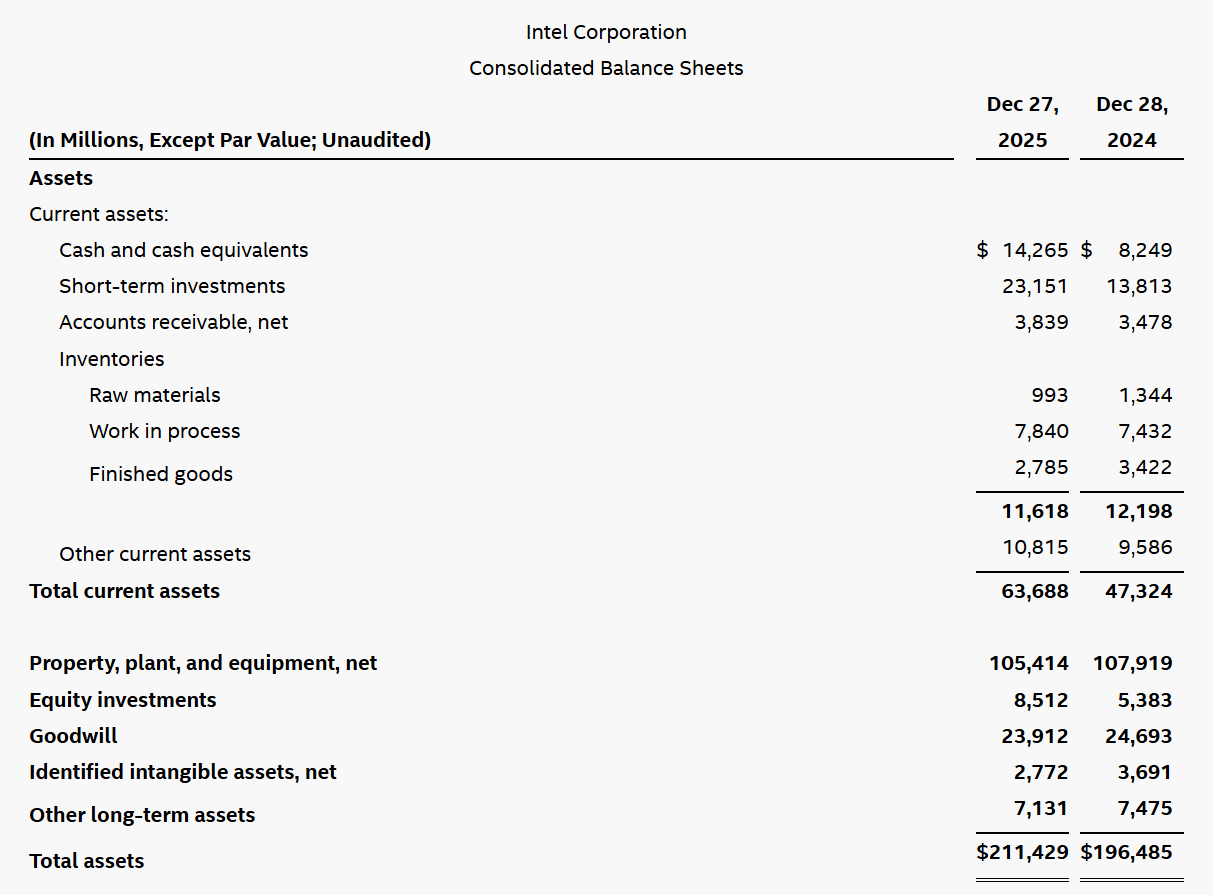

The company did generate $9.7 billion in operating cash for the full year[32], thanks to working capital improvements and cost cuts, but it heavily reinvested in fab capacity and received government offsets. Capital expenditures (additions to property, plant and equipment) were on the order of $20 billion in 2025, though net capex was lower after about ~$1.6 billion in government grants (e.g. CHIPS Act funds) and partner contributions[33][34]. Intel slashed its dividend to practically zero in 2023 to conserve cash (trailing 12-month dividend was just $0.04/share)[35], underlining its capital-intensive focus.

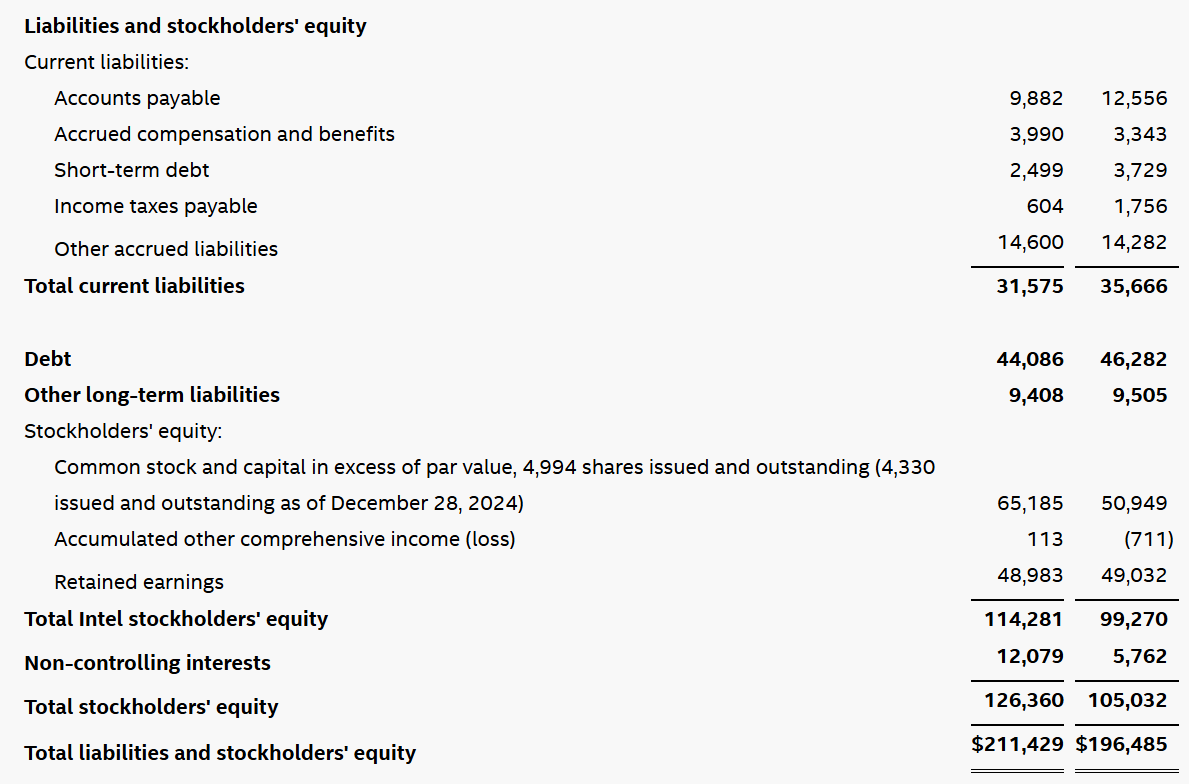

As of the latest quarter (Q4 2025), Intel’s balance sheet had $14.3 billion in cash and equivalents against $44.1 billion in long-term debt[36]. The debt load jumped in recent years as Intel raised capital to fund fab expansions and also incurred some debt for Mobileye’s spin-out.

Net debt is moderate (~$30 billion) relative to assets, and Intel has been shoring up liquidity – notably, in August 2025 the U.S. government invested $8.9 billion for a ~10% equity stake as part of the CHIPS Act support[37][38], bolstering Intel’s cash position. With that deal, Intel’s share count increased to ~4.99 billion shares outstanding[39].

The company’s financial footing is thus supported by external funding, but core cash generation will need to improve in 2026+. Management has guided for positive adjusted free cash flow in 2026, which implies a combination of modest revenue growth, margin uptick, and disciplined capex (they plan to hold 2026 capex “flat to down slightly” from 2025 levels)[40][41].

In summary, Intel’s LTM (last twelve months) fundamentals are weak: ~$53B sales, essentially zero net profit, and negative free cash flow (all as of Q4’25[26][42]). But they are inflecting: by cutting ~$4 billion in annual operating costs and stabilizing revenues, Intel stopped the bleeding in late 2025. The financial question for the turnaround is whether gross margins can recover to 40%+ and stay there, enabling $10B+ annual free cash flows again – a level necessary to comfortably fund its hefty capital needs without further dilutive financing.

Product Mental Model

Intel’s product portfolio and manufacturing are tightly interwoven, for better and worse. The company’s advantage historically was scale economics from vertical integration: design a dominant CPU architecture, produce it in high volume in owned fabs, and use the profits to fund the next generation. Scale was a virtuous cycle – high PC and server volumes drove fabs to high utilization, which spread fixed costs and kept Intel’s unit costs lower than rivals (who often had to use third-party foundries).

This is how Intel could spend ~$15–20B on R&D and still earn >50% gross margins in the 2010s.

Where scale helps is in any area where large volume reduces per-unit cost or accelerates learning. For example, manufacturing yields tend to improve faster when running lots of wafers; Intel’s huge PC business historically gave it a yield-learning edge over smaller foundries. Scale also helps amortize the massive design and software ecosystem costs – Intel’s x86 chips come with decades of software optimizations and developer support that smaller competitors couldn’t replicate. In the current context, scale is helping Intel ramp its new nodes: the company is running multiple products (client CPUs, server CPUs, chipsets) through its Intel 4 and 3 lines, providing a critical mass of wafers to debug those processes.

However, scale can hurt when it collides with complexity and fixed costs. Intel’s manufacturing is an all-or-nothing game – the fabs carry enormous fixed overhead, so if volume slips, margins collapse. We saw this in 2022–2023: PC demand fell and Intel’s utilization dropped, turning what were high-gross-margin products into loss-makers. Unlike a fabless designer that can simply order fewer wafers, Intel was stuck with underloaded fabs, directly hitting its P&L. The product strategy exacerbated this when Intel fell behind in process technology: its 10nm delays around 2018–2020 meant Intel had to stretch older 14nm products and cede the density/cost advantage to AMD (which leveraged TSMC’s 7nm).

Essentially, when Intel’s process falters, its product competitiveness and cost structure both unravel simultaneously, due to integration. We are now seeing Intel try to use its manufacturing for competitive benefit again – e.g. the new Core Ultra (Panther Lake) PC chips are built on Intel 18A and integrate an AI accelerator on-die[13], something only possible because Intel controls both design and fab to co-optimize. Similarly, Intel is using advanced packaging (EMIB, Foveros) to mix-and-match chiplets from different process nodes (including TSMC-made tiles for graphics) within one product[43][44]. This product approach – modular “tile” architectures – is a direct response to its prior scale problem: Intel realized one giant monolithic die per chip is too risky/costly on leading nodes, so it’s leveraging both internal and external manufacturing for different parts. Scale now comes from the ecosystem: e.g. an Intel CPU may use its own CPU tile plus a TSMC GPU tile; Intel’s packaging pulls it together, and the volume of the combined product still fills Intel’s package assembly lines.

Going forward, if Intel’s foundry strategy works, its product and manufacturing mental model shifts further: the fabs will make not only Intel’s own chips but also others’ chips, effectively increasing scale and de-risking utilization. One could imagine, for instance, Intel 18A fabs producing an Intel CPU, a Qualcomm mobile SoC, and a Department of Defense custom chip concurrently – diversifying the manufacturing base. This would be a sea change: Intel’s manufacturing scale would no longer depend solely on Intel’s product sales, which is exactly the model that has made TSMC so resilient. In sum, Intel’s products and manufacturing interact as a single system – when aligned, they reinforce a moat (unique features like x86 + AI on cutting-edge silicon, only available from Intel’s factory); when misaligned, they magnify losses.

The turnaround blueprint is to re-align them: get the process back on the leading edge so that product competitiveness is restored, and use other people’s product volume to buttress fab economics. That combination, if achieved, makes Intel’s integrated model extremely powerful again.

Business Model

Intel’s business model is evolving from a pure-play Integrated Device Manufacturer (IDM) (where the company profits mainly from selling its own chips) to a hybrid IDM-foundry model. Traditionally, Intel monetized through selling CPUs, chipsets, and other silicon products at a margin that reflected its tech leadership and branding. The CPU business has a relatively short duration on each product – a new generation launches roughly every 12–18 months, and pricing power historically came from being the performance leader and offering an upgrade path. Intel could price chips with hefty gross margins (60–70%) in the days of minimal competition, essentially extracting monopoly rents on x86 in segments like servers. However, that pricing power eroded when AMD 0.00%↑ caught up; Intel had to discount, and we saw average selling prices fall and margins compress.

In the emerging model, Intel Foundry Services (IFS) adds a different monetization approach: long-term contracts with customers to manufacture their designs, often with pre-payments and risk-sharing. Foundry customers typically pay for mask sets and NRE (non-recurring engineering) to get their chips up and running on the process, and then pay per wafer. Margins in pure-play foundry tend to be lower per unit than a hit product like a CPU, but the trade-off is more stable, high-volume revenue if you fill the fab. Intel is trying to position IFS not as a low-margin commodity foundry, but as a specialty provider for leading-edge and advanced packaging – meaning it aspires to TSMC-like gross margins (~50%) on that business in the long run[9].

Realistically, though, in the next couple of years foundry will be a drag on margins because Intel is essentially incubating a business: current external foundry revenue is minimal and the segment is incurring huge startup costs (e.g. duplicate PDK development, customer support engineering). Indeed, Intel’s “Intel Foundry” segment in 2025 had an operating loss of about $10 billion on ~$18 billion revenue when viewed standalone[24][45]. This reflects heavy fixed costs (new fabs, EUV tools, overhead) that are not yet absorbed by third-party volume. The company expects this to improve as they onboard customers; they even noted that advanced packaging services have seen early customer pre-payments due to tight substrate supply – a positive sign of monetization via upfront cash[46][47].

Another aspect of Intel’s model is the duration and capital intensity of returns. Building a new fab can take 3–4 years and $10–20 billion before any revenue is generated. Intel is attempting creative financing to mitigate this; for example, it brought in private capital (Brookfield Asset Management) to co-invest in its Arizona fabs in exchange for a share of future cash flows. It also negotiated the aforementioned U.S. government equity investment which provided essentially free capital in exchange for national service commitments[37][48]. These moves indicate that Intel recognizes its business model must adapt to the extreme capital intensity – it’s blending public and private funding to build capacity with less burden on its own balance sheet. Over time, if the foundry business succeeds, Intel’s revenue mix will include a higher portion of multi-year contracts (e.g. a 3-year wafer supply agreement for a customer’s chip) as opposed to purely selling its own CPUs on the open market each quarter.

This could make Intel’s revenue more backlog-driven and predictable, but also potentially lower-margin unless it maintains a technology edge. It is worth noting that foundry customers will have choices (TSMC, Samsung) and will push for competitive pricing; Intel will have to prove that its value-add (domestic location, secure supply, advanced packaging, etc.) warrants premium pricing.

In summary, Intel’s legacy business model: high upfront design / manufacturing cost, recouped by selling proprietary chips at high margin for a few years, then repeat – is being supplemented by a foundry model: get others to help pay for the fab by making their chips, locking them in with ecosystem IP and packaging, and create a more continuous revenue stream.

The long-term monetization of “Intel 2.0” would be a combination of product sales (where Intel aims to preserve some pricing power, especially in data center CPUs which can have 4-5 year lifecycles in customers’ systems) and contract manufacturing income (which could also include revenue-sharing or joint ventures, especially with government and industry partnerships).

The pricing power going forward may actually come from scarcity and geopolitics: if Intel becomes the only Western source of certain cutting-edge chips, it can command high prices not purely from tech specs but from supply security. Politically, we might see quasi-guaranteed business – e.g. defense electronics fab orders – that provide baseline utilization (perhaps not high margin but covering costs, akin to a utility model).

The capital intensity will remain high; even as Intel seeks external funding, it plans to continue investing heavily in R&D (~$18B in 2025, with guidance to hold 2026 OpEx around $16B[49]) to stay on the Moore’s Law pace. The key to the business model working is that these investments produce a sustainable advantage that either yields premium product margins or near-full fab utilization (or ideally both). If not, Intel’s model could devolve into simply chasing volume at low margin – something management is clearly trying to avoid by emphasizing discipline and a “right-sizing” of the company.

Valuation and Setup

Intel’s valuation is no longer the bargain-basement value stock it was in 2022; it’s now a show-me turnaround premium. At the Jan 23, 2026 close of $45.07, Intel trades at about 4.3× LTM sales[67] and ~20× EV/EBITDA (on depressed earnings) – rich relative to its own history. For most of the 2010s, Intel traded around 3x sales and 10–12x earnings; at one point in late 2022 it was <2x sales when pessimism peaked. The market is clearly pricing in a return to growth and margin expansion. On a forward P/E basis, the stock is ~46× 2026 consensus EPS[2], but that reflects the fact that 2026 earnings are still expected to be low (roughly $1.00). If Intel executes, forward estimates will rise; for instance, looking out to 2027–28, some analysts model ~$3+ EPS, which would put the forward multiple in the mid-teens. In other words, the current valuation anticipates a lot of earnings growth – but that growth is feasible if things go right.

Comparatively, Intel is cheaper than pure-play foundry leader TSM 0.00%↑ on price/sales (TSMC trades around 7–8× sales) but far more expensive on earnings for now (TSMC is ~18× forward P/E with ~55% gross margins[9], reflecting its established status).

It’s notable that Intel’s EV ($246B) is roughly half of Nvidia’s annual revenue – showing how differently the market values a dollar of sales for a struggling IDM versus an AI darling. This setup suggests that if Intel’s turnaround even partially succeeds, there is room for valuation uplift. For example, if Intel can reclaim ~45% gross margins and say 15% operating margin (which is still below its historical peak), on $60B revenue that would be ~$9B operating income. With interest and taxes, maybe $7B net, ~ $1.40 EPS. Arguably a company with strategic importance and growth prospects could trade at 20× that, or $28/share – which would actually be a lower stock price than today, highlighting that a lot is riding on even better performance or a higher multiple.

The bull case is that Intel could eventually earn $3–4 EPS (with margins approaching TSMC levels and higher revenue from foundry), at which point even a market multiple of ~18× would justify ~$60–$70 stock, and a hype multiple (if it’s seen as a unique asset) could go higher.

The bear case is that Intel muddles around breakeven and the market re-rates it back to ~2× sales – which on $50–55B sales would be $100–110B market cap, less than half of today’s (implying a stock in the low $20s).

From a setup perspective, the stock’s sentiment has done a 180. A year ago, almost every sell-side analyst had a Hold or Sell on Intel and it was the most underweighted name in semiconductor portfolios. Now, upgrades have poured in – we’ve seen multiple upgrades in Jan 2026 alone, with price targets ranging widely (some bears still at $30, bulls up to $60)[68][69].

The U.S. government’s 9.9% ownership (now the largest shareholder) also changes the setup: it provides something of a backstop both psychologically and literally (the government paid ~$20.47/share for their stake[71][72], which could be seen as a floor in a dire scenario, and politically there may be moves to support Intel if needed). Intel has thus become part of the “MAGA trade” – a stock championed as aligned with the U.S. industrial policy zeitgeist. Under the Trump Administration, it’s not just a company but a strategic asset; this has drawn in a new class of investors who see patriotic or policy-driven upside, which can buoy valuation beyond pure fundamentals. However, one must be cautious: trading on politics can cut both ways (e.g. future administrations or public backlash could impose constraints).

Technicals

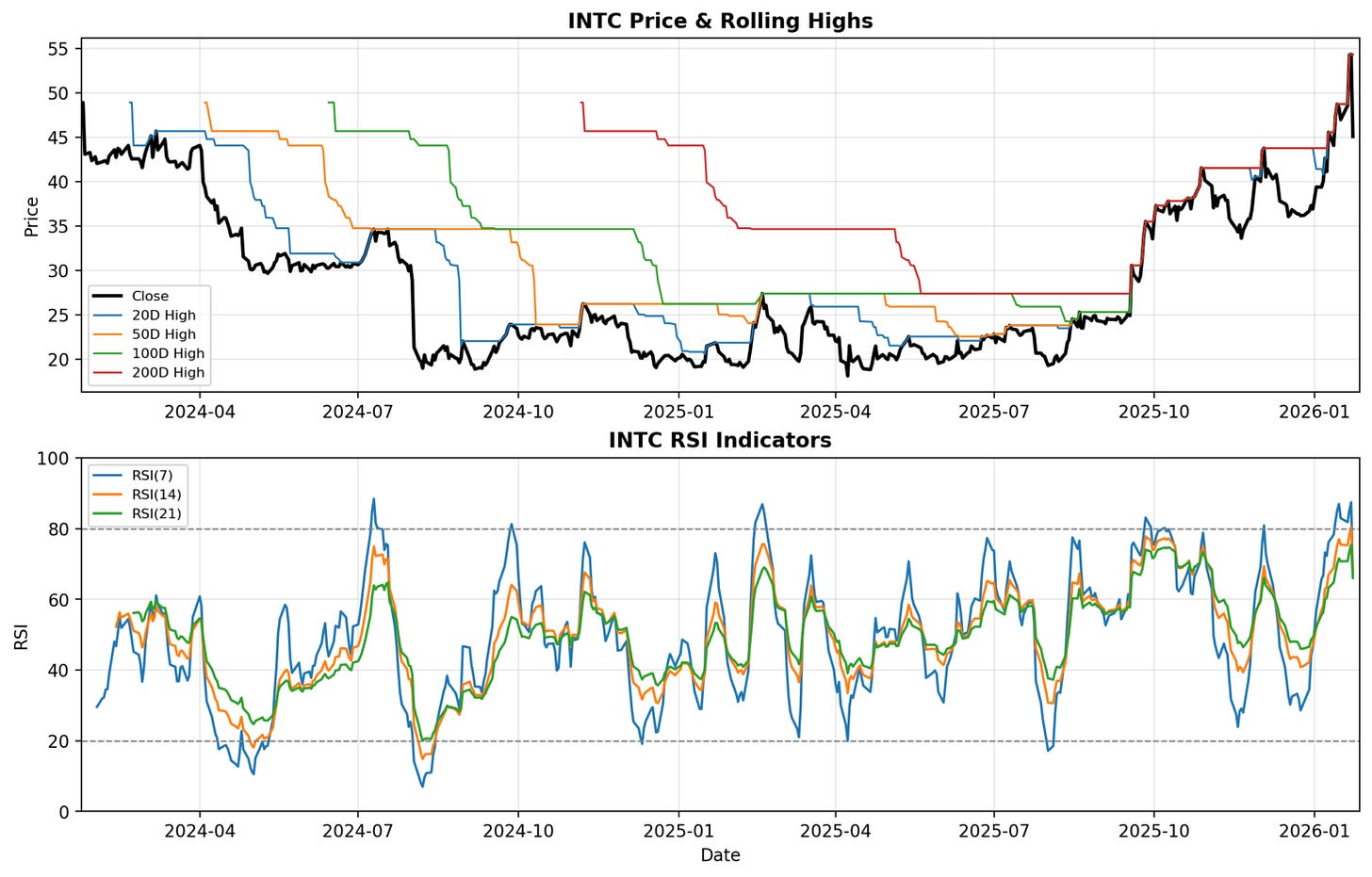

Despite the 18%+ drawdown following the latest earnings, INTC 0.00%↑ technicals looks quite strong.

Intel’s stock has been in a strong uptrend since mid-2025, but is now encountering some volatility around key levels. After a steady climb, the stock hit a 52-week high of $54.60 in January 2026[1], reflecting bullish momentum into the Q4 earnings report.

However, that report – despite solid results – came with cautious guidance, sparking a sharp pullback. The stock fell 17% in a single day on Jan 23, 2026 (from ~$54 to ~$45[73]) on concerns about Q1 supply constraints.

This high-volume reversal (nearly 291 million shares traded, 3× average volume[74]) punctured the short-term overbought condition (RSI dropped to ~52 from the high-60s[75]). Technically, the stock is now testing its 50-day moving average, which it is still slightly above – as of last close, Intel traded about +12.5% above its 50-day MA and +3.7% above its 20-day[76]. This suggests the uptrend is intact but has moderated. Impressively, Intel remains ~55% above its 200-day moving average[77], a testament to how powerful the rally off the 2023 lows has been. Typically, such a large gap to the 200-day indicates extended momentum, though the recent pullback is working off some of that froth.

Chart-wise, support levels might cluster around the low-$40s – notably, the government’s buy-in price around $20 is far below and probably only relevant in a true crash, but more immediately the stock had a consolidation zone in the $37–40 range in late 2025 (post-Q3 earnings). If the stock continues to fade, that zone could be a support band.

On the upside, the mid-$50s now represent overhead resistance; the stock will need a new catalyst (perhaps an earnings beat or a big customer announcement) to break to new highs above $55. The trend structure is higher highs and higher lows since 2023, so even after this pullback, the series isn’t broken – a low in the $40s would still be above last autumn’s ~$35 level, keeping the uptrend line intact.

Momentum indicators have cooled but are not bearish: RSI ~52 as noted, MACD (if observed) likely just had a bearish cross due to the earnings drop, but that could flip back if the stock stabilizes and bounces. The 200-day SMA is still rising, which often means longer-term momentum investors stay in the trade as long as price is above that average.

One important technical consideration is that Intel’s rally had a significant sentiment component – it became a bit of a momentum trade tied to AI hype and nationalist investment themes in late 2025, which means technicals and fundamentals were interacting.

For instance, as Intel’s stock climbed, it likely forced shorts to cover and quant funds to buy (trend-following quants, etc.), which further boosted momentum.

Now with the stock off highs, some of those players may trim or flip, which can exacerbate short-term swings. The current technical condition could be described as “momentum in check, trend still positive.”

Volume on the sell-off was huge, which can indicate a near-term capitulation by weak hands. If $45 holds and volume tapers off, it could mark a tradable bottom in this correction. Conversely, if selling continues on high volume through the 50-day, it would signal that the sentiment shift is deeper and perhaps tied to fundamental doubts (like worries about Q1 results or macro).

Key Drivers (6–12 Months)

Over the next year, several key drivers will determine Intel’s trajectory and whether the turnaround thesis gains traction or stalls:

Quarterly Earnings and Guidance: Each earnings report in 2026 will be scrutinized for margin improvement and revenue stabilization. Key will be gross margin trends (Q1’26 is guided to ~34.5% non-GAAP[78], with improvement expected from Q2 as supply constraints ease[79]) and any upside in revenue from recovering demand. If Intel can consistently beat its conservative guidance as it did in recent quarters[66], confidence will build. Watch especially Q2 and Q3 2026 results – by then, the CPU shortage issues should abate and we’ll see normalized demand vs supply.

Foundry Milestones & Customer Announcements: In mid-2026, Intel is expected to announce further foundry customer engagements. Any public deal with a marquee customer will be a huge catalyst – for example, if Qualcomm confirms it’s tape-out on Intel 20A/18A for a mobile chip, or if AWS and Intel detail a partnership for cloud ASICs. Intel has also guided to start risk production on Intel 14A in 2026–27 and more advanced packaging offerings[56][80]; progress there (like a successful 14A test chip) would signal staying on roadmap. Additionally, pay attention to external wafer volume ramp – if Intel discloses that, say, a noticeable percent of its wafer output in late 2026 is for external clients, that will show the foundry strategy bearing fruit. Conversely, if 2026 goes by with no major customer win announced, that would be a negative.

Product Ramps and Competitive Launches: Intel will be launching its Sierra Forest and Granite Rapids data center processors (Intel’s first major chips on the “Intel 3” node) in 2026. These products’ reception by cloud customers is a driver – early indications of design wins or benchmarks showing parity with AMD’s offerings (e.g. AMD’s Zen 5 EPYC) will bolster the thesis that Intel can regain share. In PCs, the adoption of Core Ultra (Panther Lake) in holiday 2026 laptops will be a litmus test: if reviews highlight its AI capabilities and efficiency (thanks to 18A) and OEMs market it heavily, it can drive a PC upgrade cycle and validate Intel’s process lead. Also, watch GPU/AI accelerator progress – Intel’s next-gen GPU (Arc series for clients or Ponte Vecchio successor for datacenter) and its Gaudi3 AI chip uptake. Although smaller, any traction there (or lack thereof) signals how well Intel can diversify beyond CPUs.

Supply Chain and Capacity Dynamics: Ironically, one driver in 2026 is the “CPU shortage” that emerged from the AI boom. Intel indicated that demand for its server CPUs outran supply in Q4’25 and Q1’26[81][61]. As it adds capacity in Q2 onward, watch how this plays out: if demand stays strong and Intel can meet it by mid-2026, we could see a significant bump in data center revenues (pent-up orders being filled). However, if broader component shortages (DRAM, substrate) persist[82], it might cap PC shipments and thus Intel’s client CPU sales. Essentially, if the AI boom keeps driving higher core-count server builds, that’s a tailwind for Intel’s Xeon line – as long as it can allocate enough wafers to those chips. Intel is prioritizing server over low-end PC chips in allocation[83], which suggests near-term mix improvement (good for margin). The trend of AI inference moving to CPUs (with large language model agents etc.) is also a driver that Intel cited – if that becomes a tangible growth area, it could expand CPU TAM. In summary, strong demand environment plus Intel’s capacity coming on line could yield upside surprises in 2H 2026.

Policy and Subsidies: Government and policy support will continue to be a factor. In the next 6–12 months, how the CHIPS Act funding is distributed and utilized matters – Intel is expecting additional grants or tax credits (e.g. an investment tax credit for fab spending). If a new U.S. administration or Congress pushes even more incentives for onshore production (or conversely, if there’s any backlash to the Intel deal), that could affect Intel’s economics. Right now it appears the Trump Administration is fully behind Intel (even floating ideas like more government purchases or requiring federal agencies to source domestic chips). Any export control developments can also drive business Intel’s way – for instance, if restrictions on China accessing advanced tech tighten further, some companies might shift to Intel for “safe” supply of certain chips not subject to bans. Also, Europe’s initiatives (Intel is building fabs in Germany with subsidies) and how those progress will be news to watch; a final approval of German subsidies or EU contracts could improve sentiment.

Macro and End-Market Recovery: At a higher level, the state of the PC and server end markets over the next year will drive results. PC demand seems to be bottoming after the pandemic bust; any revival in corporate PC refresh or consumer upgrade (perhaps spurred by Windows 11 AI features or just replacement cycle) would directly lift Intel’s CCG revenues.

Risks and Reversals

While the upside case is compelling, there are several critical risks that could break the thesis or cause a major reversal in Intel’s fortunes:

Execution Risk – Process & Product: This is the foremost risk. Any slip in Intel’s process technology roadmap would be devastating to the narrative. For instance, if Intel 18A suffers an unexpected yield regression or delay (e.g. a defect issue requiring redesign), it would not only hurt Intel’s own product launches but also shatter the nascent trust among foundry customers. Likewise, product execution missteps such as a flawed chip design (bugs or performance shortfalls in new CPUs) could derail momentum. Intel has a history of product delays (e.g. Sapphire Rapids’ late launch); a recurrence of such delays for Granite Rapids or Panther Lake would remind investors of “old Intel” problems. Essentially, the turnaround leaves very little margin for error – a single major failure could unravel confidence built over the last two years.

Competitive Pressure: Intel faces very strong competitors who are not standing still. AMD remains a significant threat in both PCs and especially servers. If AMD’s next-gen Zen 5 or Zen 6 processors outperform Intel’s at key metrics (price, performance per watt), Intel could continue to lose or fail to recapture share, which would pressure margins and revenue. AMD has been leveraging TSMC’s process lead; if TSMC 3nm/2nm stays clearly ahead of Intel 18A in real-world chip performance, AMD will exploit that. There’s also the risk of ARM-based competition: Nvidia’s Grace CPU for servers and Amazon’s in-house Graviton CPUs have started carving niches. Thus far x86 ecosystem and software inertia have limited their impact, but that could change – if a major cloud or enterprise shifts a workload to ARM en masse, it undercuts Intel’s x86 stronghold. Similarly, Apple’s success with its M-series ARM chips in Macs could inspire a vendor like Qualcomm (backed by Nuvia acquisition) to re-enter high-end laptop or server chips around 2026. Such competition could eat into Intel’s TAM or force it into price wars.

Geopolitical and Regulatory Risk: While Intel benefits from U.S. government support, there are risks here too. One is overreliance on government largesse – if political winds change (for example, if a future administration or Congress is less enthusiastic about essentially subsidizing Intel), the company could lose some financial cushion or face strings attached. The government stake itself is unusual; it could invite scrutiny or populist criticism (as seen by some calling it “corporate socialism”[88][89]). Regulatory risk also includes antitrust or competitive practices: ironically, if Intel comes roaring back, it might once again draw antitrust fire (as it did in the 2000s) for trying to lock in customers or stifle AMD. Another geopolitical risk is with China – roughly 25% of Intel’s revenue historically came from China/Hong Kong. U.S.-China tensions could result in China favoring local chip suppliers or AMD (which, being fabless, can still supply China from TSMC for now), potentially hurting Intel’s sales in that market. Moreover, if China were to retaliate against U.S. tech sanctions by restricting rare earth materials or equipment Intel needs, that could disrupt production. And of course, the Taiwan situation is a double-edged sword: while a conflict would massively benefit Intel in relative terms, it would also likely cause a global recession and supply chaos that could hurt everyone in absolute terms. It’s a hedge for Intel, but a very risky one for the world.

Financial & Balance Sheet Stress: Intel has taken on significant debt and obligations while its cash generation is currently minimal. If the turnaround takes longer than expected, prolonged negative free cash flow could strain the company. It might have to raise more capital – diluting shareholders further or adding debt.

Thesis Durability / Narrative Risk: The current market narrative around Intel is optimistic and somewhat brittle – it won’t take much to swing sentiment back to pessimism. If Intel hits even a minor bump (like guiding slightly below expectations in one quarter, or a rumor of a yield issue), it could puncture the bullish narrative and cause a rush to the exits given the stock’s strong run. The risk is that Intel’s turnaround is a multi-year story but market patience may not be multi-year if progress isn’t linear. There’s also the risk of investor fatigue: if by mid-to-late 2026 Intel’s improvements aren’t clearly translating to earnings (e.g. still barely break-even), investors might conclude that the stock’s gains were unjustified and rotate out, especially if other semiconductor plays (like AI chips) offer more excitement. The “MAGA trade” element could likewise reverse – if the political narrative changes or if Intel becomes a political football (imagine debates about government ownership in an election year), that could introduce volatility or stigma. Additionally, key person risk: CEO Lip-Bu Tan and his team (including CFO David Zinsner and the technology leaders) are critical – if any of them were to depart abruptly or if there were signs of internal discord (not unheard of at Intel’s board level), confidence could suffer.

In essence, the risks boil down to execution and environment. Intel needs to execute near-flawlessly in a competitive environment that will push back at every step.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Intel today represents a high-stakes bet on a self-reinforcing turnaround driven by technology leadership. The fulcrum variable – successful execution of the 18A process and the winning of external foundry trust – will determine whether the company enters a new virtuous cycle or falls back into stagnation. If Intel can sustain its recent progress, each step forward can unlock the next: solid 18A yields enable competitive CPUs; competitive products regain market share and pricing, which improves margins; improved cash flow funds the next node (20A/14A) and attracts more foundry customers, which further boosts scale and economics. That positive feedback loop could lead Intel, by 2028, to look like a very different company – one with TSMC as a peer in manufacturing and Nvidia/AMD as peers in products, essentially a hybrid titan commanding both design and fab capabilities. In that scenario, today’s valuation would prove modest.

However, this outcome is not predestined – it must be earned through unrelenting execution in the face of heavy competition and high capital demands. The path is highly path-dependent: a single serious stumble on the critical “fulcrum” could break the loop, sending Intel back into a reflexively negative cycle of low utilization, lost customers, and financial strain.

In the arena of semiconductors, the line between a renaissance and a false dawn is narrow – Intel is walking that line now, with the market and history watching.

Really thorough breakdown on the foundry pivot. The framing of 18A as the make or break fulcrum is spot on, and frankly something alot of the bullish coverage glosses over. The foundry losses at that scale are hard to ignore even with government backstop. Been following Lip-Bu Tan's execution closely since Q3 and the stock reaction post-earnings shows how little room for error ther is.

Great analysis of a company I have put in the too hard pile, thank you.

Be interesting to assign probabilities to the various outcomes. My worry would be that a challenged balance sheet and a fickle administration (the CEO went from almost being deported to getting a big check) put you on the express to mid $20s if there’s even a whiff of poor execution. This Q4 stumble might show the short leash investors have on this one.