Soros vs. Modern Multi-Strats: Correlation, Capital, and the Business Model Shift

A thought exercise

We all have people we look up to – heroes whose examples shape how we think and act. In life, mine are my parents; if I can accomplish even a fraction of what they’ve achieved, I’ll consider myself fortunate. As a guitarist, my hero is Steve Vai. The point is that having figures to emulate matters – people who have already walked the path and left a blueprint worth studying. In investing, the arena that now consumes most of my mental bandwidth and will for years to come, my heroes are George Soros and Stanley Druckenmiller.

The past couple of weeks, I’ve been reflecting on how Soros and Druckenmiller ran money – a style I aim to emulate – and how starkly it contrasts with the way today’s hedge fund behemoths, and even many large newly launched funds, operate.

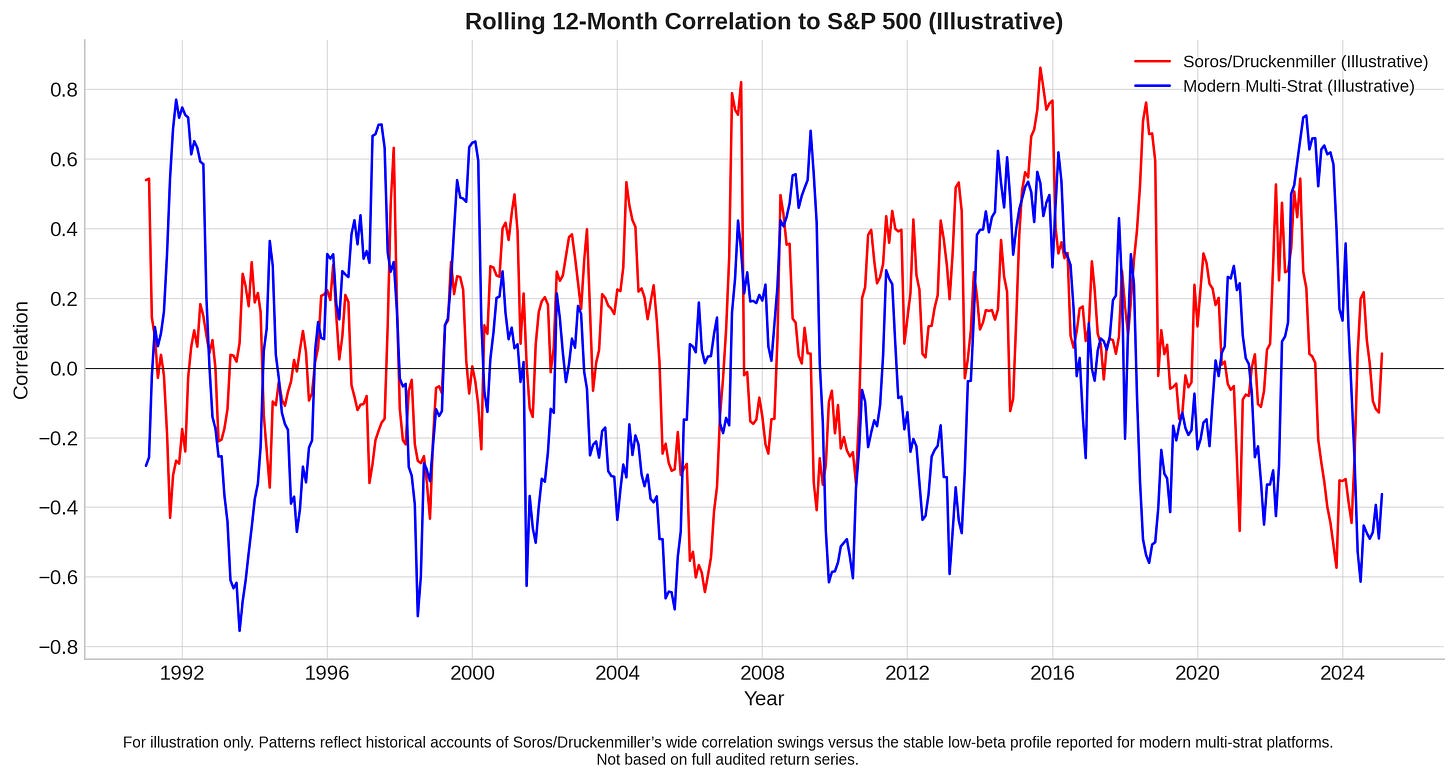

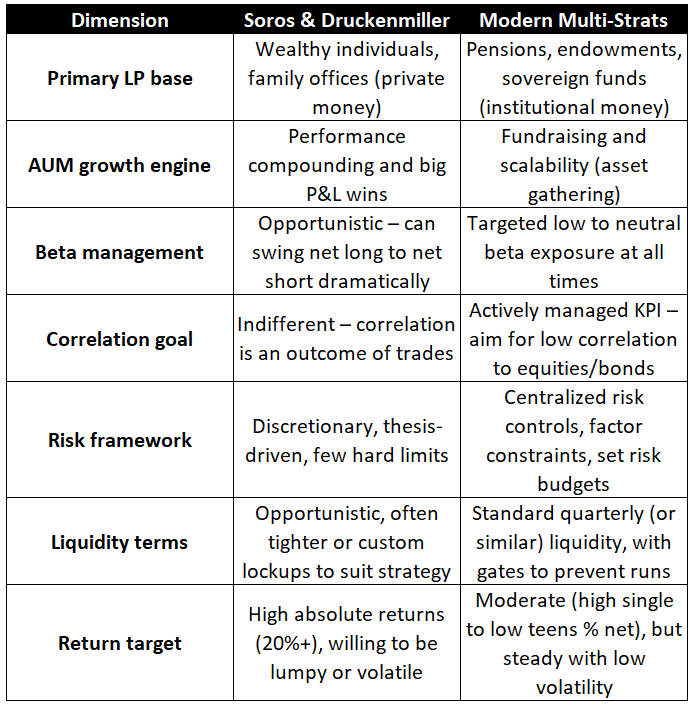

Soros and Druckenmiller optimized for absolute returns with enormous flexibility, treating beta and correlation as incidental outcomes of their convictions. They swung hard when conviction was high and reversed quickly when the facts changed. In contrast, today’s multi-strategy hedge fund giants engineer portfolios for stable Sharpe ratios, low correlation to traditional assets, and scalable capacity.

The difference starts with the source of capital and what those investors demand. Modern institutions – pensions, endowments, sovereign funds – prize smooth, low-beta returns that fit liability schedules and pass board scrutiny. This has driven a structural shift in hedge fund business models: Soros and Druckenmiller grew assets through performance and bold, reflexive bets, while today’s platforms scale through fundraising, capacity, and correlation control. For allocators, the lesson is as follows: mandate design and capital source will dictate whether a fund is built to chase asymmetry or to deliver a predictable, low-correlation return stream.

Before launching my hedge fund and digging into the modern hedge fund model, I dismissed it outright. I didn’t believe the next George Soros, Stanley Druckenmiller, Warren Buffett, or Bill Ackman would be working inside these firms given their mandates. Even Ken Griffin and Steven A. Cohen didn’t build their legacies inside multi-strat platforms.

To be fair, with my real estate private equity background, I was never likely to get hired at one anyway – so maybe part of me was rationalizing my own lack of prospects. We’ll never know for sure.

What I do know, after speaking with many HNWIs and institutions, is this: the key is knowing which game you’re playing from day one. The game I want to play – and will gladly play for decades – is delivering strong absolute returns, scaled to the largest amount of capital my psychology, opportunity set, and luck will allow.

How Soros and Druckenmiller Ran Money

Soros and Druckenmiller epitomized the unconstrained global macro mandate. Running Soros’s Quantum Fund, they had the latitude to go anywhere – long or short any asset class, in size – based purely on their macroeconomic theses. Beta exposure (market direction) could swing wildly from net long to net short, and correlation to equity markets or other benchmarks was an outcome, not a target.

What mattered was being right on the trade and aggressively sizing it. Soros famously said he doesn’t have fixed rules; he adapts to the environment and looks for “changes in the rules of the game”. This discretionary, thesis-led style meant Soros and Druckenmiller would “bet the ranch” when conviction was high, tolerating volatility and drawdowns as the price of outsized gains.

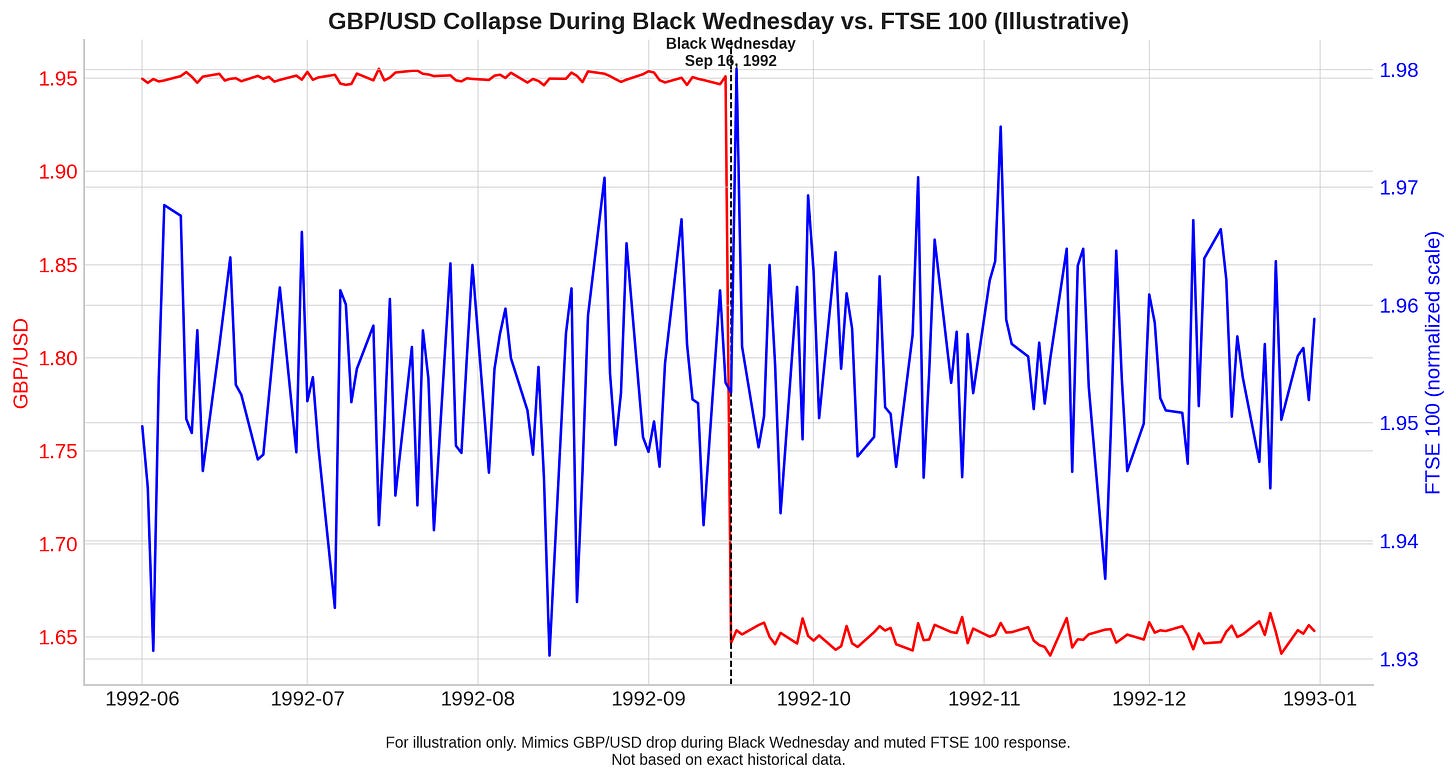

For example, Soros’s Quantum Fund took on the Bank of England in the 1992 ERM crisis. Sensing the British pound was fundamentally mispriced in the exchange-rate mechanism, Soros poured the fund’s capital into shorting the pound. On September 16, 1992 – “Black Wednesday” – the UK was forced to devalue and exit the ERM. Quantum reportedly made over $1 billion profit in that single month by shorting the pound (and other European currencies). This trade had essentially zero correlation with the equity market’s performance; it was a pure macro currency play, yielding enormous absolute return while stock indices were largely irrelevant to the thesis. The pound’s collapse was caused in part by Soros’s trade (a hallmark of his reflexivity theory, where his actions reinforced the outcome). The scale of the win – Soros “broke the Bank of England” – illustrates how indifferent these macro managers were to volatility or benchmark tracking. What counted was the payoff.

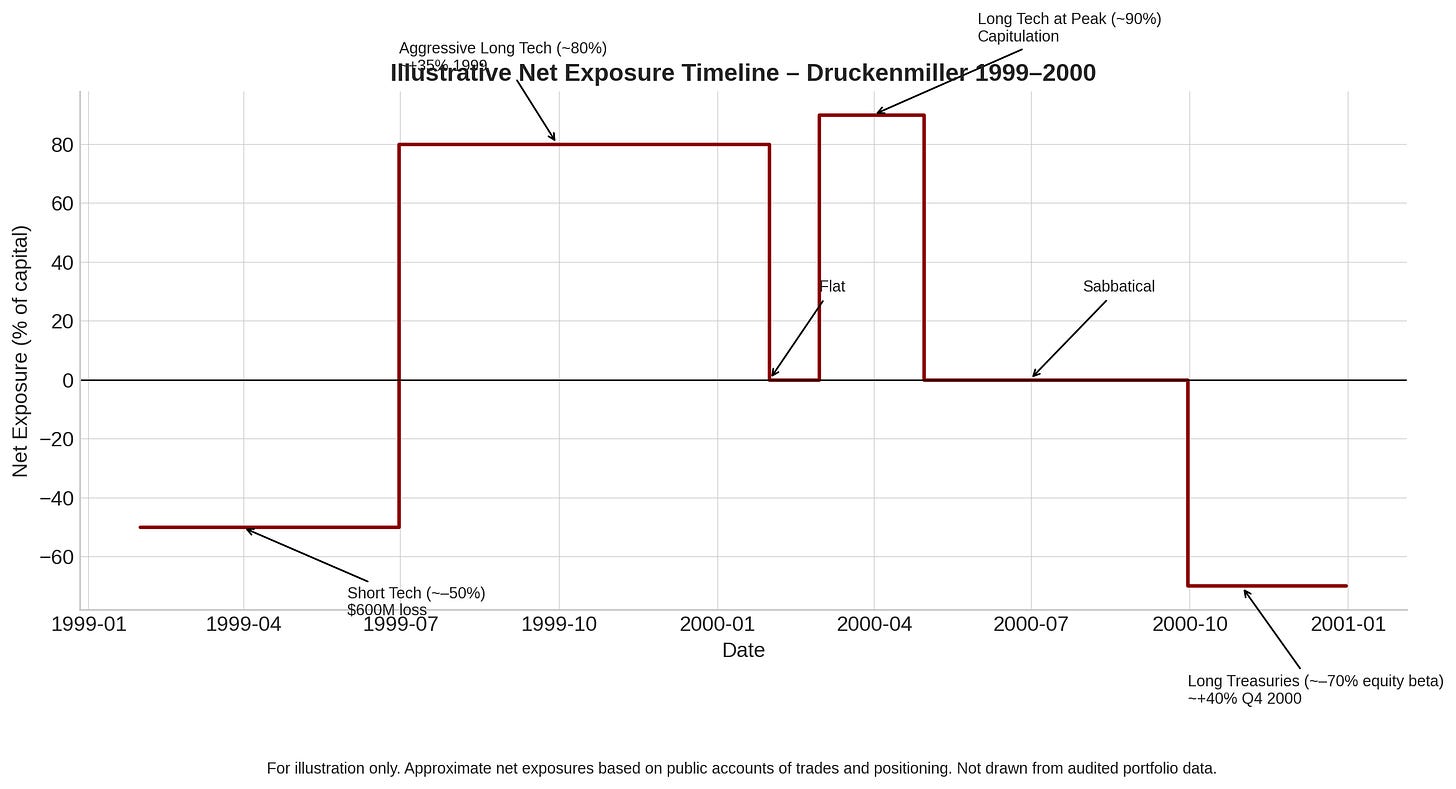

In early 1999, while running Soros’s Quantum Fund, Druckenmiller saw internet stocks as a mania. He built roughly $200 million in shorts, only to watch them surge higher. Within weeks, those positions had turned into about a $600 million loss, leaving Quantum down in the mid-teens. Rather than double down, he pulled the shorts, reassessed, and brought in younger “gunslingers” to help chase the trend he had underestimated. By the second half of 1999, Quantum was aggressively long tech, finishing the year up around 35% while the Nasdaq Composite gained roughly 85%, its best calendar-year performance on record.

In January 2000, still at Quantum, he concluded valuations were “crazy” and sold out of tech. But as the rally kept running into March, he capitulated, putting roughly $6 billion back into high-flying names - what he later called buying “an hour before the top.” The Nasdaq collapsed weeks later, and Quantum lost billions in the reversal. By April 2000, after that blow, Druckenmiller resigned from Quantum.

He stepped away from markets entirely, taking a months-long sabbatical in Africa. When he returned in September 2000 to focus solely on his own firm, Duquesne Capital, he saw oil, interest rates, and the dollar all rising while forward earnings looked vulnerable. He took a massive duration bet, about 350 percent of ten-year equivalents long in Treasuries, and made roughly 40% in the fourth quarter of 2000.

The sequence shows how quickly he could flip positioning when conviction shifted. In the space of 18 months, he went from net short tech, to aggressively long, to flat, to back in at the peak, to fully out and long bonds in size. Correlation to equities swung from positive to negative multiple times, because correlation was never the objective - the thesis and the sizing drove the book.

This tolerance for volatility was a hallmark of the Soros era of macro. Another anecdote: on February 14, 1994, Quantum Fund was caught wrong-footed when the U.S.–Japan trade talks collapsed. Soros (and Druckenmiller, his deputy) had bet that the Japanese yen would continue to weaken against the dollar, but when talks broke down, the yen surged 5% in one day. Quantum lost an estimated $600 million that day. The funds were down about 2.7% for the year after that hit. Rather than seeing this as a failure of risk management, Soros’s team shrugged it off. A rival hedge fund manager noted that such a loss was “fairly normal volatility given the nature of these funds’ big trades”.

Indeed, Quantum had been up 60–70% the prior year and averaged ~40% annual returns in recent years, so they could stomach a 3% dent as the cost of doing business.

This highlights a key difference: Soros and Druckenmiller accepted large drawdowns and volatility if the potential upside of a trade was even larger. Risk was managed by conviction and Soros’s intuitive feel (famously, Soros said he’d get back pain when a position was going wrong), not by targeting a volatility number or tracking error.

Throughout the 1990s, Soros’s macro funds were involved in every major dislocation – not out of a desire for non-correlation, but because that’s where the money was to be made. In 1997, during the Asian financial crisis, Quantum Fund famously wagered nearly $1 billion against the Thai baht’s peg to the dollar. The baht was fixed at 25 per USD; Soros built short positions via forward contracts, effectively going long the dollar/baht in expectation of a devaluation. He was right – Thailand ran out of reserves and floated the baht, which plunged. Soros was accused of “breaking the Bank of Thailand” much as he had in England. Neighboring countries’ equities imploded in the crisis, but that was incidental damage from a currency thesis.

The Quantum Fund didn’t mind if those trades had zero correlation with global stock indices – if anything, Soros’s currency shorts were a hedge against complacent equity markets. (In fact, Soros’s funds also took losses in that period in other markets; e.g., Quantum reportedly lost $2 billion in the 1998 Russian financial crisis when Russia defaulted. Big gains and big losses were part of the ride.) Soros explicitly pursued reflexivity: he looked for situations where his investment could cause or amplify the fundamental move – such as speculative pressure causing a currency regime break.

This style is hard to reconcile with maintaining a smooth P&L – Soros once quipped that being right or wrong doesn’t matter; what matters is making more when right than you lose when wrong. The Quantum Fund’s long-term record (30%+ annualized over decades) came from a few huge hits and some large drawdowns, not from grinding out steady monthly gains.

My understanding of their approach to markets is the following: Soros and Druckenmiller ran money in a performance-first paradigm. They cared about absolute return and the asymmetry of payoffs, not whether their monthly returns had a low correlation to the S&P 500 or a stable volatility. Beta was something to dial up or down opportunistically – Druckenmiller might be 200% gross long one month and net short the next. Correlation was ignored except insofar as it affected the opportunity (indeed, some of their best trades had no relation to stock market movements). Their mandate from their mostly private clients was to maximize returns, and those clients accepted that Soros’s fund might be up 50% one year and down 10% the next.

This old-school model of hedge fund aligns with a certain type of capital – often UHNW individuals, family offices, and proprietary capital – that tolerated volatility for the chance of dramatic gains.

The Allocator Revolution and the New Product Spec

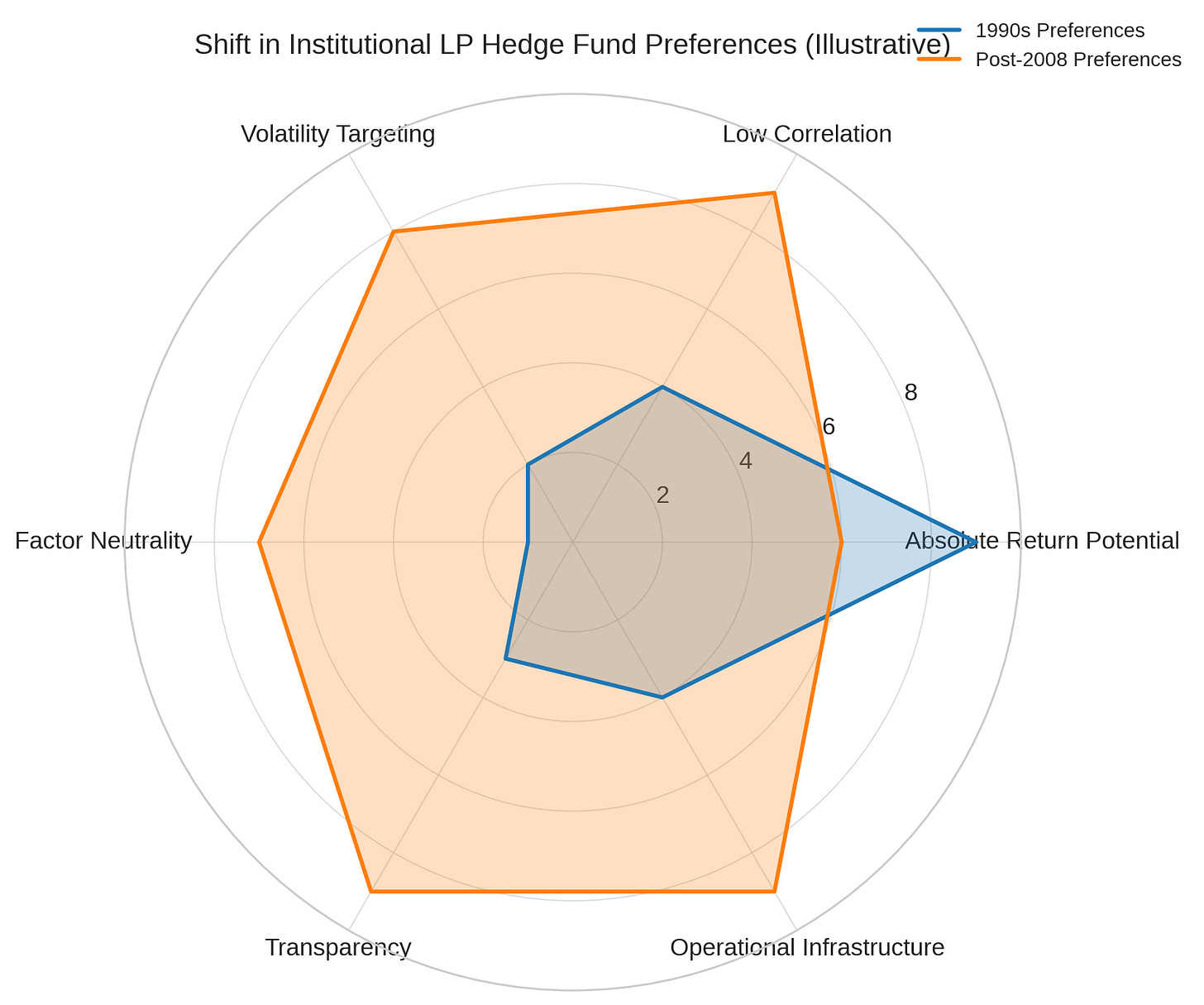

Around the turn of the millennium, the hedge fund investor base underwent a sea change. In the 1980s and 90s, hedge funds were largely backed by wealthy families and private capital looking for high-octane returns. But post-2000, and especially after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, institutional allocators like public pension plans, university endowments, foundations, and sovereign wealth funds became the dominant LPs in hedge funds. These institutions brought a very different set of requirements and constraints. They weren’t looking for a rollercoaster ride of absolute returns; they wanted diversification, risk control, and consistency to meet their liability-driven goals.

As one Bloomberg piece noted, investors increasingly “plow money into funds that don’t rely on the next macro genius or star stockpicker, but instead offer an army of traders” delivering steady outcomes. In fact, in recent years, the large multi-strategy funds (Citadel, Millennium, Bridgewater, D.E. Shaw, etc.) have attracted essentially all net new inflows to the hedge fund industry. This allocator revolution created a new product specification for hedge funds: low correlation to traditional assets, moderate volatility, predictable liquidity, and institutional risk management.

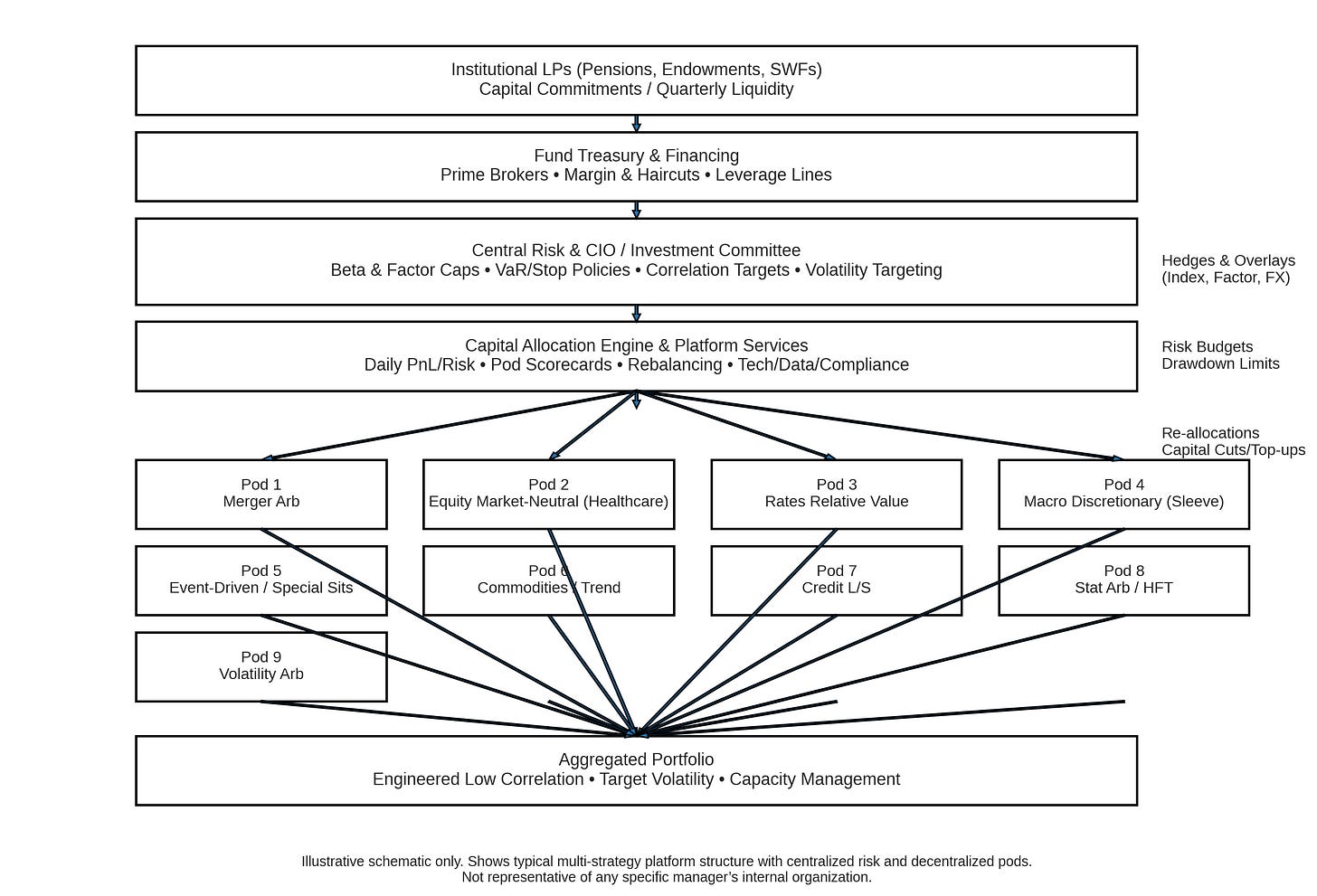

Multi-strategy “pod” hedge funds emerged as the answer to these demands. A multi-strat platform is an investment firm that houses dozens (even hundreds) of small teams or “pods” of portfolio managers, each trading a slice of capital independently, under the oversight of a central risk management system. Rather than one CIO making all the calls (as Soros did), these platforms decentralize trading to many specialized PMs – for example, one pod might do merger arbitrage, another trades equity market-neutral in healthcare, another runs a rates futures RV book, and so on. Crucially, the platform management imposes strict risk and correlation controls on each pod and on the overall fund. The goal is to combine many uncorrelated strategies so that the aggregate fund produces a smooth, low-volatility return stream with minimal correlation to broad markets.

These multi-manager funds actively target low beta and low correlation. It’s not left to chance – it’s a KPI. The central risk team monitors factor exposures daily. For example, a platform will hedge out “unwanted exposures” like directional equity beta if a few pods collectively have it. They enforce risk budgets for each pod, meaning a PM can only use so much leverage or VaR, and drawdowns are met with capital reductions or hard stop-outs. The platform continually rebalances capital to PMs based on risk-adjusted performance. If one strategy is making uncorrelated alpha, it might get more allocation; if another starts correlating with, say, equities and underperforming, it might be cut.

The result is an engineered overall portfolio that delivers what institutions want: absolute return and attractive risk-adjusted returns in almost any market environment. Many multi-strats explicitly design themselves as all-weather funds (coined by Ray Dalio of Bridgewater) aiming for mid-high single digit volatility and steady performance. They “ensure, for example, that all unwanted exposures are hedged and that the independent managers stay within risk budget guidelines. Simply put, many Multi-PM funds consistently deliver their investment objective and target volatility.”

Another hallmark of the new product spec is liquidity terms and gates that align with institutional needs. Big allocators typically want at least quarterly liquidity to fit their asset-liability management. However, the multi-strat managers also need to lock in stable capital – they do not want fickle hot money that could force redemptions at exactly the wrong time. The compromise has been standard hedge fund liquidity (quarterly or annual windows) often coupled with gate provisions and longer notice periods. In practice, multi-strategy platforms use strong contractual gates to prevent a run on the fund in a crisis. They aim for “stability of capital”, even if that means terms more onerous than needed for the underlying assets.

Many multi-strats are levered and rely on the confidence of not having to liquidate positions quickly. By having investor-level and fund-level gates, they ensure that capital cannot flee en masse during stress periods. This is a direct response to 2008, when many single-strategy funds with liquid portfolios still had to suspend redemptions due to panic. Institutional allocators accept these gates up front as the price for accessing a well-run, low-volatility fund – it’s baked into the product now.

The rise of consultants and board governance also influenced the new spec. Pensions and endowments often invest via consultants who apply rigorous due diligence and checklists. They favor managers who tick certain boxes: documented risk controls, a history of not blowing up, moderate fee terms, transparency, etc. A swashbuckling macro cowboy wouldn’t pass many institutional investment committee reviews today. Instead, the ideal is an “institutional quality” operation. This has pushed hedge funds to formalize everything – from volatility targeting (e.g. aiming for a 6% annualized vol and adjusting exposures to keep it there) to factor neutrality (ensuring the fund isn’t implicitly long momentum, short value, etc., beyond limits). Some multi-strats even cap their correlation: for instance, they might run scenarios to estimate if the fund’s beta to equities in a downturn would stay below 0.2 or some threshold. The mantra is “no surprises” for the LPs.

Crucially, the investor base now is far more focused on correlation as a feature. Large institutions already have plenty of equity and bond exposure. When they allocate to hedge funds, they are seeking diversification. A multi-strat that can deliver, say, a +8% annual return with near-zero correlation to equities is extremely attractive to them. It provides a smoother ride for the overall portfolio (in theory). Post-2000, especially post-2008, many investment committees explicitly ask: How will this fund perform if our equities drop 20%? Will it offset losses or exacerbate them? Funds got the message – those that could position as “uncorrelated absolute return” gathered billions, while pure directional macro funds often struggled with outflows if they hit a bad year.

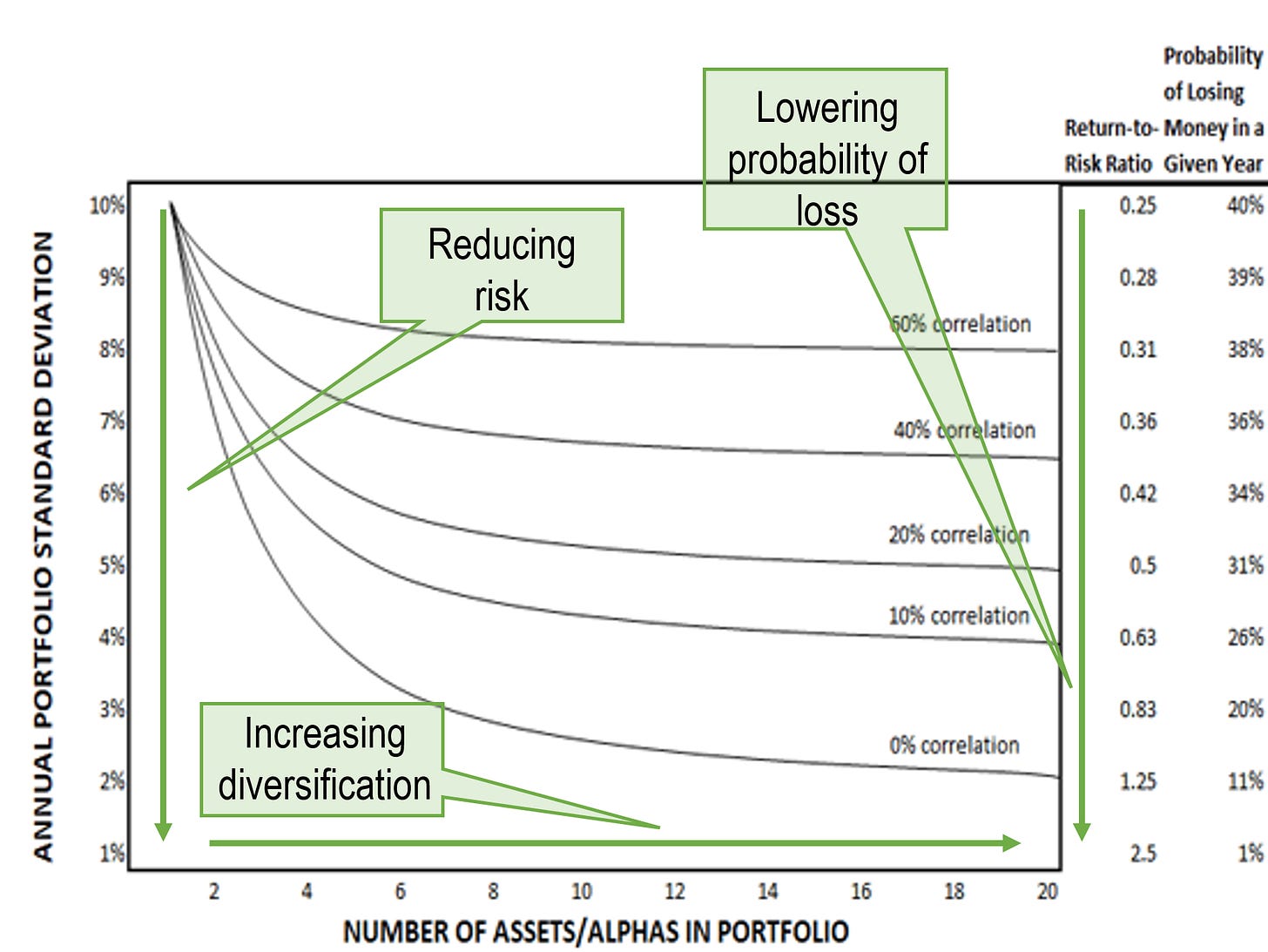

The pod model industrialized this low-correlation promise. By putting many strategies under one roof, the idea is that idiosyncratic wins and losses will average out. A multi-strat platform might have one pod losing 5% on a credit trade at the same time another pod makes 5% on an oil spread trade – the fund nets out flat, with low volatility. It’s the classic diversification benefit, made systematic. What’s different from a naive diversification is the centralized risk overlay: management actively reallocates and cuts risk to ensure the whole doesn’t drift into a correlated bet. As The Hedge Fund Journal noted, pod shops maintain “very strict risk limits on equity market beta, style and factor exposures, as well as position sizes” to keep the system in check. The modern platform is as much a risk management company as an investment company.

To illustrate the contrast, consider the table below comparing Soros/Druckenmiller-style macro versus the modern multi-strat platform:

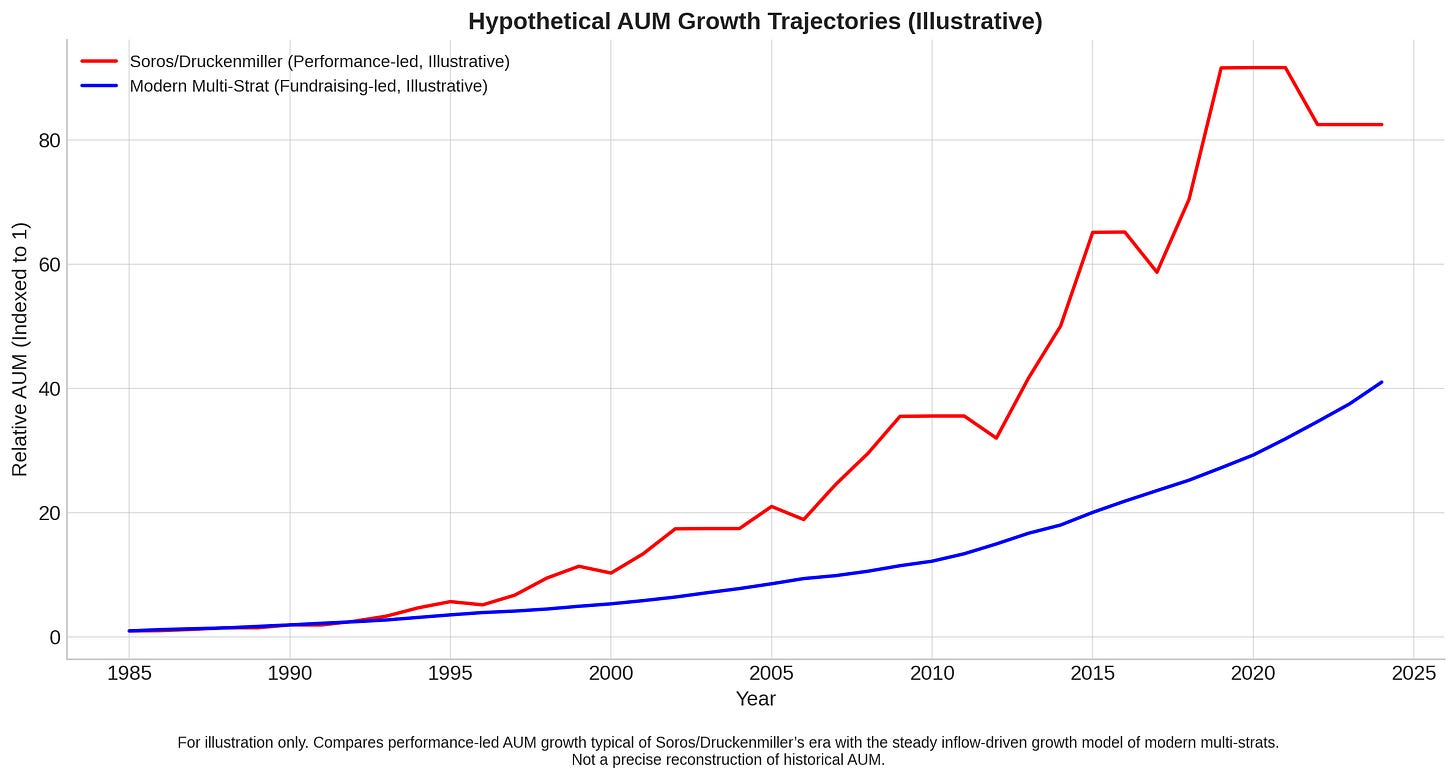

Business Model Math: Performance vs. Asset Gathering

The divergent approaches are rooted in business model incentives. In Soros and Druckenmiller’s heyday, a hedge fund’s AUM grew primarily by making a lot of money for investors. Soros started with a few million in the 1970s; by compounding at 30%+ annually and attracting some additional capital, Quantum Fund swelled into the billions. But a huge portion of that growth was internal – performance fees and reinvested profits. There was little need (or sometimes ability) to aggressively market the fund. In fact, Soros closed the Quantum Fund to new outside money for long stretches, focusing on managing the capital he had.

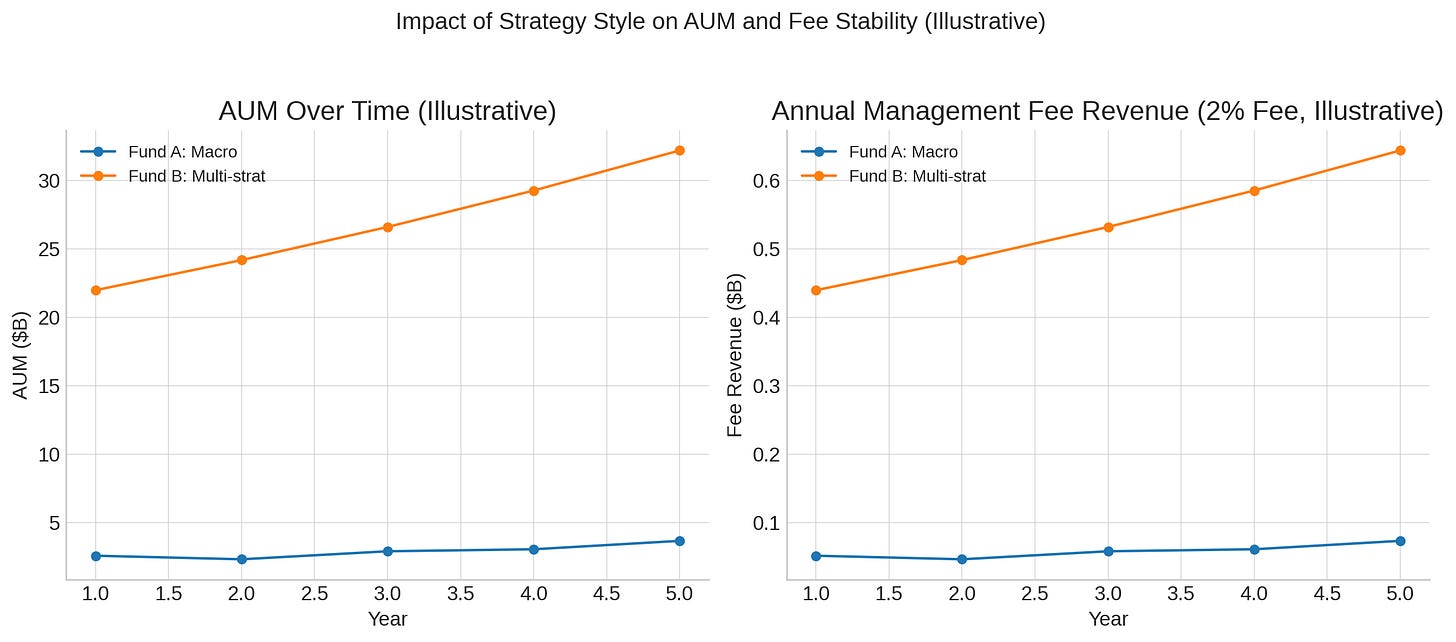

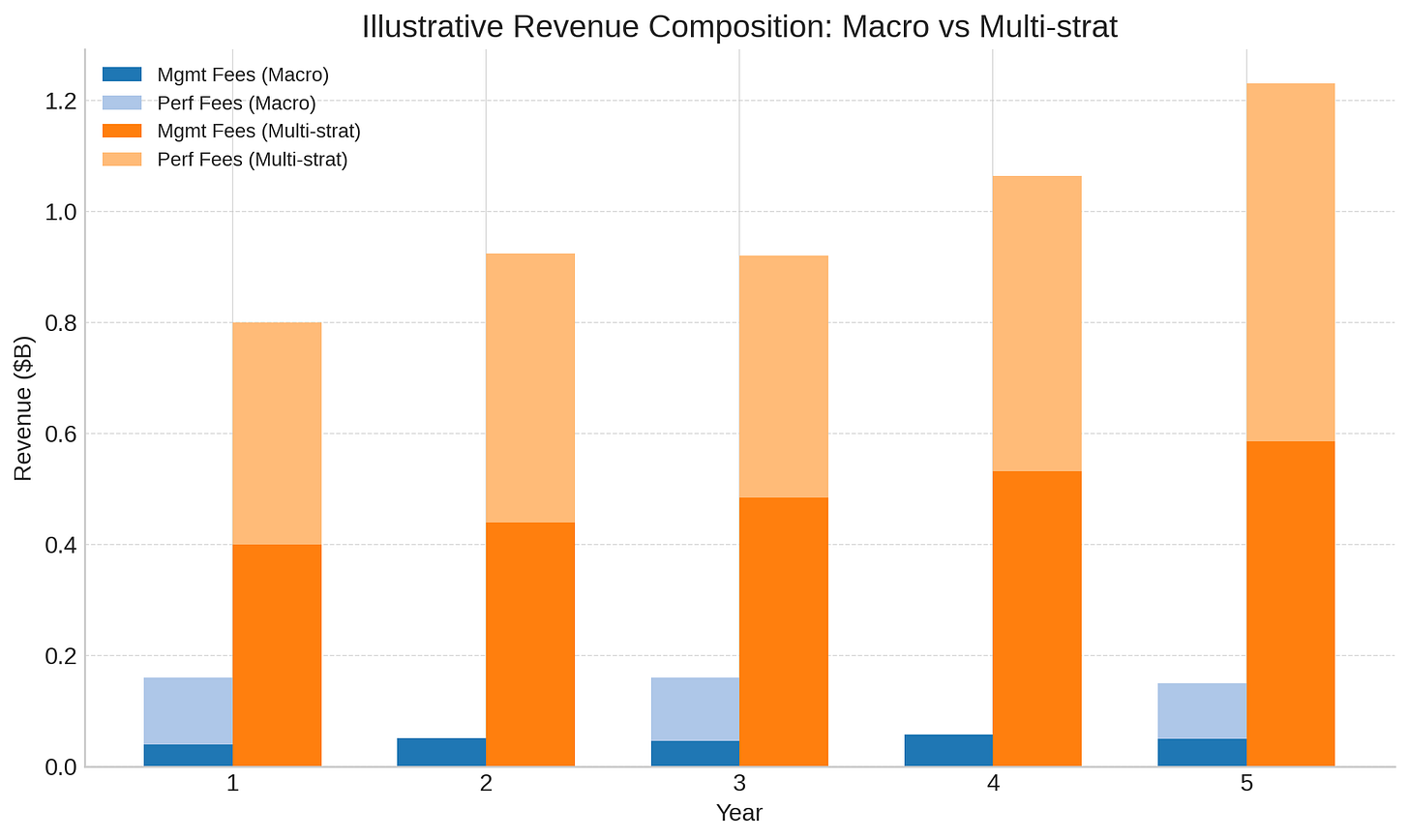

Today’s multi-strategy platforms, in contrast, are built to scale up by bringing in outside capital. The founders of these firms (Ken Griffin of Citadel, Izzy Englander of Millennium, etc.) realized that a business which steadily returns ~10% net with low risk can attract tens of billions of dollars from institutions. The margin on that is extremely lucrative: management fees of 2% on $20 billion is $400 million a year, before performance fees. So whereas Soros might have made his fortune purely by performance (e.g. earning 20% of a $1 billion profit), modern platform owners make a fortune by collecting fees on a large asset base that they carefully protect from downside. It’s a fundraising-led growth model.

One analysis by Goldman Sachs showed multi-manager firms grew AUM 175% from 2017 to 2023, while the rest of the hedge fund industry grew only 13% – a testament to asset inflows chasing those stable results.

This shift in AUM growth engine changes everything about how hedge funds are run. If your goal is to maximize fee-earning AUM, you prioritize capacity and consistency. A macro trader might turn $1 billion into $2 billion in a year with a huge bet – but then the strategy might not scale beyond $2B, or might lose 30% the next year, causing investor redemption. A multi-strat aims to deliver, say, 10% every year on a growing asset base of $5B, $10B, $20B… The compounding of management fees and modest performance fees on a large stable AUM can actually create more franchise value over time than the volatile boom-and-bust of a macro fund.

For example, consider two scenarios: Fund A (macro) makes +30% one year, -10% the next, +25% the next, etc., averaging ~15% with high volatility on $2B of capital. Fund B (multi-strat) makes +10% like clockwork on $20B of capital with very low volatility. From an owner’s perspective, Fund B generates a steadier income (2% of $20B = $400M management fee, plus performance fee on the 10% gain) and can keep scaling via new allocations. Fund A might generate high performance fees in a good year, but also risk losing AUM in a bad year (investors pull out after -10%). Indeed, multi-strat firms often have far more stable fee revenue, which supports reinvestment in technology, talent, etc., further entrenching their advantage.

The capacity factor is critical. Soros’s style was spectacular but not infinitely scalable – there are only so many billion you can deploy on a single currency bet without moving the market (Soros bet $10B against the pound and effectively hit the limit of market impact). Modern multi-strats avoid concentrated bets and instead multiply many small uncorrelated bets. This means if you’re running $30B and want to grow to $50B, you can add more pods, more leverage, or new strategies to absorb that capital without drastically reducing returns. There is of course a limit (as multi-strats have learned – at some size, alpha can dilute, and some have even returned capital to avoid crowding). But generally, the business model math favors being a platform: a 10% return on $50B yields $5B gross profit, of which maybe $1B+ flows to the manager in fees – and it’s repeatable. Soros’s one-time $1B win on Black Wednesday was legendary, but a platform can make a Soros-level profit every year with much less volatility by virtue of scale.

Fees themselves have adapted to this model. Many multi-manager funds charge the classic “2 and 20” (2% management, 20% performance), but some have introduced pass-through fees where each pod’s costs and payouts are passed to investors, effectively ensuring PMs are paid on their own performance. The key point is that management fees now play a larger role in total revenue. For macro funds, performance fees in big years were the jackpot (e.g. Soros’s cut of that $1B Black Wednesday profit). For multi-strats, management fees on a huge AUM base provide a floor of profitability, and performance fees add on during good years. This makes the firm’s economics more predictable and durable. It also incentivizes the firm to prioritize asset growth so long as returns don’t slip too much.

Why the Shift Persists

This transformation in hedge fund style persists because it is reinforced by both investor preferences and the market environment. First, the collective trauma of crises like 2000–02 and 2008–09 left deep scars on institutional memory. Many pension trustees and endowment boards lived through 30–50% equity drawdowns and saw certain hedge funds blow up or gate redemptions in 2008. There is now a strong bias in favor of “smoother paths” of returns. A fund that can show a track record with very few down months and shallow drawdowns is far more likely to win an institutional mandate than a fund with a higher arithmetic return but big swings. Board governance plays a role – a university endowment board is more comfortable with a fund that has, say, a Sharpe ratio of 2 and no worse than -5% in a quarter, because it won’t get them in the headlines or cost someone their job. Consultant frameworks formalize this by scoring funds on things like Sharpe, downside deviation, beta to equities, etc. Multi-strats score well on these metrics by construction (e.g. multi-manager funds as a group have had significantly lower volatility and correlation to equities than other hedge funds in recent years). This means consultants keep recommending these funds, which keeps the cycle going.

Second, competition and alpha decay in the markets have made it harder for a single trader to dominate year in, year out. In the eras of Soros’s great calls, markets like FX had fewer players and occasionally big mispricings (the UK ERM policy failure, for example). Today, markets are more efficient and crowded with algorithmic and institutional players. Large global macro trades still happen (e.g. the big short on subprime in 2007, or various trend-followers riding 2022’s bond crash), but it’s rarer to find a reflexive trade where one fund can shift a central bank’s course. Alpha opportunities tend to be smaller, more fleeting, and spread across many niches. This environment favors a breadth of strategies rather than a few concentrated bets. Multi-strats are built to harvest many small alphas – they employ hundreds of PMs looking for tiny edges in every market. The value of a robust risk system and the law of large numbers is higher now. If pure alpha is harder to come by, squeezing out a Sharpe of 0.5 from 100 different uncorrelated trades can produce a very smooth high-Sharpe composite.

In other words, the multi-strat model is a rational response to a lower-alpha world: if you can’t easily find a 30% annual trade, find thirty 1% trades and package them with low correlation.

Additionally, the post-GFC regulatory environment indirectly encouraged the multi-strat approach. With interest rates super low for a long time, institutions needed alternatives to meet return targets, but they also became more risk-aware. Multi-strats positioned themselves as “bond substitutes” or “diversifiers” that could give, say, 7–10% with low risk – appealing when bonds yielded ~2-3%. They also often offer tail risk management or at least a narrative of being market-neutral (though how they actually perform in a crisis is the real test). Notably, many multi-strats proved relatively resilient in events like the 2020 COVID crash – they had a rough March 2020 (some funds dropped a few percent and delevered) but generally avoided catastrophic losses and many quickly rebounded by year-end. This further reinforced allocator confidence that these platforms have crisis playbooks and can manage through storms with only modest damage. (That said, it’s important to note that correlation isn’t dead – in a severe market shock, correlations tend to spike even for multi-strats. March 2020 showed that when liquidity dries up, many supposedly uncorrelated strategies all suffer at once, and platforms had to cut risk fast. Platforms try to mitigate this by stress-testing and keeping some dry powder, but a liquidity crunch tests everyone. The difference is multi-strats design their funds to survive such crunches with gates and rapid de-risking protocols.)

Another reason the shift persists: the platform model’s success breeds further success (and barriers to entry). The top multi-strat firms have become huge, with resources to recruit top talent and invest in technology. It’s an arms race – as Goldman Sachs noted, big multi-managers use their scale and fees to “attract talented personnel, expand strategies, and build cutting-edge infrastructure”. This makes them even harder to compete against for smaller single-manager funds. Many talented traders who in an earlier era might start their own fund now choose to join a Citadel or Millennium pod where they get a guaranteed allocation and upside without having to raise capital or run a business.

The entrepreneurial macro startup route is less common now; even those who try often end up converting into a multi-strat model or joining one (e.g. many ex-prop and ex-hedge fund traders have migrated into pods). Thus, the platform model consolidates talent, which further entrenches its performance (or at least its ability to deliver on the low-vol promise through sheer diversification). Meanwhile, the survivorship bias looms large: for every Soros or Druckenmiller, there were other macro funds that flamed out (examples include Niederhoffer’s fund blowing up in 1997, LTCM’s demise in 1998, and countless smaller macro funds that shut after losses). Those high-profile blowups also nudged investors toward the seemingly safer multi-strat approach. The legendary macro managers are indeed legendary – they’re exceptions. The average macro fund did not deliver Soros-like results and many closed. Investors and managers have internalized this: it’s safer to play a strong defense (diversified, risk-controlled) than to go for the home run that might strike out.

None of this is to say that discretionary macro is “dead” or that multi-strats are unequivocally better. But the industry’s center of gravity has moved. Hedge fund mandates today are often crafted with explicit language about low correlation, volatility limits, and diversification roles. The multi-strat platform is the embodiment of those objectives, which is why its footprint keeps growing.

Implications for Managers and LPs

For managers, the contrast between these models highlights a crucial choice: what mandate and capital do you align with? A talented trader who thrives on big directional bets might chafe under the constraints of a multi-PM platform (and might be better off in a macro fund structure or running family money). Conversely, a manager who values stable economics and team collaboration might prefer the platform route.

The incentives dictate behavior – if you take in pension money and promise low correlation, you must build the systems and culture to deliver that. If you choose to run a high-octane macro fund, you must accept a more volatile asset base and a niche set of investors who can stomach it.

There are still times when correlation agnosticism wins. Certain market regimes favor bold macro plays – for instance, the period of 2022–2023 with rising inflation and rate volatility saw some macro funds post record gains (e.g. trend-following CTAs and global macro funds had strong returns, in some cases outperforming multi-strats). When a huge dislocation occurs (a major war, a debt crisis, etc.), a nimble macro trader with conviction can dramatically outperform the more constrained, diversified funds. In these moments, being “correlation indifferent” – willing to take on beta or directional exposure – can yield uncorrelated returns of a different kind (uncorrelated because no one else has them!). So it’s not that one approach is strictly better; it’s about matching the approach to the environment and the mandate. As an allocator, one might want a mix: some steady multi-strat allocations and a couple of true macro gunslingers for when lightning strikes.

LPs also need to discern where “low corr” is genuinely diversifying versus where it might be a closet bet. Not all low volatility funds are truly uncorrelated. Some may simply be short volatility or running carry trades that do fine in normal times but blow up in a crisis (in hindsight, some supposedly market-neutral funds in 2007 were actually long credit risk, for example). A multi-strat’s advertised low beta could conceal hidden tail risks – e.g. crowding in similar trades across pods or reliance on continuous liquidity. Allocators should press to understand: is the fund making idiosyncratic alpha (e.g. relative value trades, arbitrage, etc.) or is it implicitly dependent on benign markets? Truly diversifying low-correlation product will have structurally different drivers than equities or bonds – whereas a fund that sells crash insurance will look uncorrelated until the crash when correlation jumps to one.

From a portfolio construction perspective, mandate design is paramount. An institution should decide: do we want an “absolute return” sleeve aiming for high standalone returns (even if volatile), or do we want a “diversifier” that’s lower return but offsets our other risks? Soros-style funds fit the former – they aim to generate high returns and can justify a place if you are okay with higher volatility. Multi-strats often fit the latter – a replacement for part of your bond/equity portfolio to reduce overall risk. The mistake would be expecting Soros-like returns from a multi-strat or expecting bond-like stability from a macro fund. Each has a role.

Finally, for both managers and investors, alignment of expectations is critical. A manager should be upfront about what they optimize for (Sharpe vs. total return, etc.), and an investor should align with a manager whose incentives match the investor’s goals. If an allocator demands low correlation, they must accept that the fund might not shoot the lights out in bull markets (the fund might lag a roaring equity market because it’s hedged). Conversely, if one backs a macro maverick, be prepared for dry spells or big swings – that’s the ride you signed up for.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the evolution from Soros and Druckenmiller’s era to the age of multi-strats ultimately comes down to who your capital partner is and what mandate you choose. Soros and Druckenmiller ran a performance-centric, reflexive mandate funded by capital that cherished big absolute returns.

Today’s multi-strat platforms operate a productized, risk-managed mandate catering to institutions that prize steadiness and diversification. Neither is categorically “better” – they are different answers to different investor preferences.

The lesson for both managers and allocators is to be deliberate in mandate design and partner selection. A hedge fund’s behavior (swinging for the fences or smoothing the path) will always follow the incentives set by its capital. Design the mandate right, choose your capital partners wisely, and you pick the trade-off that fits your objectives – whether it’s chasing the next big macro trade or engineering an army of uncorrelated alphas. The key is knowing which game you’re playing from the start.

Great overview of the evolution of hedge funds over the past decades - very insightful! Would you say ADFM is primarily macro with a mix of multi-strat, or effectively all macro?