Few U.S. equities are more misunderstood—or more reflexive—than Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Nearly two decades into conservatorship, these GSEs remain the linchpin of American housing finance, their destiny bound to Washington politics and Wall Street risk appetite.

This memo is for those ready to cut through the illusion: to parse the capital stack, map the legal minefield, and model what most won’t. We treat FNMA and FMCC as potential capital pivots—if, and only if, the politics and math finally align.

The goal: distill signal from noise, clarity from complexity, and conviction in a trade the market long ago wrote off as unsolvable.

Executive Summary

Figure: Treasury Draws vs. Dividends: Since 2008, Fannie Mae has drawn $119.8 billion from the U.S. Treasury but paid $181.4 billion in dividends, an excess of ~$62 billion (an >11% ROI for taxpayers through 2019). Freddie Mac similarly paid $119.7 billion vs. $71.6 billion drawn. Both GSEs have rebuilt significant net worth (Fannie $98.3 billion, Freddie $62.4 billion as of Q1 2025) through retained earnings, yet remain undercapitalized relative to new regulatory requirements.

Key Financial Metrics (Q1 2025): Fannie Mae earned $3.7 billion and Freddie Mac $2.8 billion in quarterly net income, reflecting steady guaranty fee revenues on their $4.1 trillion and $3.6 trillion mortgage credit books, respectively. Net worth has grown ~20% year-on-year for each GSE (Fannie $98.3 billion; Freddie $62.4 billion). Credit quality remains strong (average loan-to-value ~50% for Fannie’s single-family loans, 0.56% serious delinquency).

However, regulatory capital shortfalls persist – combined Tier 1 capital of ~$147 billion vs. a required ~$328 billion (including buffers) as of Q3 2024. The Treasury’s senior preferred stock claims continue to grow with retained earnings (now $216.2 billion for Fannie, $132.2 billion for Freddie in liquidation preference), and the government still holds warrants for 79.9% of common shares. Common and junior preferred shares trade at a fraction of par value, reflecting these claims and policy uncertainty.

Capital Structure & Warrants: There are 1.16 billion Fannie Mae common shares and 0.65 billion Freddie Mac common shares outstanding. The U.S. Treasury holds senior preferred stock (with a combined $348 billion liquidation preference) and warrants to purchase ~80% of each GSE’s common stock for a nominal price.

Valuation Scenarios: We outline two dominant scenarios – Recap & Release vs. Status Quo – along with variant outcomes. Below is a high-level risk/reward matrix:

Risk/Reward Summary: The common stock is a high-volatility, binary bet on political outcomes. It could multi-bag (5–10× over time) if a shareholder-friendly recapitalization occurs under the current administration, but also carries a real risk of near-total loss or reversion to penny-stock status if reform stalls. Preferred shares offer a relatively safer claim in a successful recap (more likely to be honored near par value) but still face political risk (they could be left in limbo or restructured in less favorable ways). Current pricing of junior prefs (~40¢ on the dollar) reflects both significant upside in a settlement and ongoing uncertainty. The Treasury’s warrants and senior preferred stake virtually guarantee dilution for common shareholders in any outcome, but also represent the government’s incentive to execute a value-unlocking privatization (the Treasury could net >$250 billion from selling its stakes). We assign roughly even odds to an attempted “recap and release” in the next 1–2 years versus a continued holding pattern, and a smaller probability to alternative resolutions (utility model or congressional action). Investors should size positions accordingly, prepare for binary outcomes, and monitor key catalysts closely.

GSE Background

Mandate & Business Model: Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Assoc.) and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp.) are government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) chartered to provide liquidity and stability to U.S. housing finance. They purchase residential mortgages from lenders and guarantee securitizations (Agency MBS), ensuring the flow of credit in the mortgage market. In simpler terms, the GSEs operate a guaranty fee model – they earn steady fees (average ~50 basis points of loan balance) for assuming credit risk on ~$7.7 trillion in mortgages. This marks a shift from the pre-2008 era when they also held large portfolios of mortgages and MBS for investment; today, ~80% of revenues derive from the guaranty business (versus <25% in 2011) as they have de-risked and shrunk retained portfolios. The core franchises are (1) Single-Family credit guarantee (the bulk of business, ~$3.6 trillion Fannie / $3.1 trillion Freddie single-family loans, supporting ~50% of all U.S. mortgages), and (2) Multifamily housing finance (apartment loan guarantees, ~$0.5 trillion each). These enterprises operate with a thin capital base (historically <1% of assets) under an implicit government backing.

Capital Structure (Pre-2008 vs. Now): Fannie and Freddie historically issued common stock and various series of non-cumulative preferred stock to private investors, supplementing modest retained earnings to support their guarantees. In September 2008, amid the housing crash, both were placed into conservatorship under the newly created FHFA (Federal Housing Finance Agency). Treasury rescued the GSEs via the Senior Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements (PSPAs): Treasury committed to cover net worth deficits up to $445 billion combined, ultimately investing $189 billion by 2012 ($119.8 B Fannie, $71.6 B Freddie). In return, Treasury received senior preferred shares (initial liquidation preference equal to the amount invested) accruing a 10% dividend, plus warrants for 79.9% of each company’s common stock (strike price $0.00001). These terms effectively gave the government nearly all future economic upside while diluting existing shareholders.

Conservatorship Era (2008–2019): From 2008–2011, Treasury’s infusions shored up the GSEs’ balance sheets as credit losses mounted. By 2012, as housing stabilized, Fannie and Freddie returned to profitability. Rather than allow recapitalization, the Net Worth Sweep (Third Amendment, Aug 2012) redirected 100% of their net profits to Treasury as dividends, beyond the 10% originally required. This meant any earnings did not rebuild equity for public shareholders – a controversial move later judged in court to have “arbitrarily and unreasonably” violated shareholder rights (see Legal Overhang). Through 2019, all GSE profits were swept quarterly, which led to cumulative Treasury dividends of about $300 billion (Fannie ~$181 B, Freddie ~$119 B) against the $189 B invested. As a result, by 2018 the GSEs had essentially no capital buffer (net worth near zero, aside from small reserve allowances) and remained entirely dependent on Treasury’s backing to avoid insolvency.

2019–Present (Retained Earnings and ERCF): In late 2019, under the Trump administration, Treasury and FHFA amended the PSPA to allow Fannie and Freddie to retain earnings and rebuild capital up to certain limits. The GSEs have since produced consistent profits (29 consecutive quarters of net income through Q1 2025 for Fannie) and have rebuilt a combined $160+ billion in net worth. However, the PSPA changes also stipulated that Treasury’s liquidation preference increases by the amount of retained earnings – effectively accounting for those forgone dividends. This has grown Treasury’s senior pref claims to ~$340 B by Q3 2024 (and ~$348 B by Q1 2025). In parallel, FHFA under Director Mark Calabria (2019–2021) implemented a new Enterprise Regulatory Capital Framework (ERCF) in 2020, requiring bank-like capital levels (~4% of assets plus buffers). As of Q1 2025, the capital requirements are roughly $187 B for Fannie and $141 B for Freddie (risk-based, including buffers) – far above their current equity. This underscores that, despite improved balance sheets, the GSEs are still leveraged ~140:1 assets-to-common equity (or ~20:1 against total capital including Treasury’s stake). They cannot exit conservatorship until they meet these capital thresholds or have a credible plan to do so.

Policy Context: Since 2008 the GSEs have remained in limbo – private corporations with public charters, under government control. The conservator (FHFA) wields broad power to direct their operations and even disregard shareholder interests (as seen with the net worth sweep). The U.S. government – via FHFA and Treasury – effectively controls all material decisions: capital allocations, dividend policies (currently suspended), and strategic initiatives. The implicit federal backing means Fannie and Freddie’s MBS carry near-sovereign credit perception, which has been critical to housing market stability. Yet, this arrangement was always intended as temporary. Policymakers have long debated options: recapitalize and release the GSEs as private entities (preserving their role with safeguards), versus comprehensive housing finance reform (which could replace or heavily restrict them). Over 2008–2023, multiple legislative attempts to replace the GSEs (e.g. Corker-Warner, Johnson-Crapo bills) failed to pass. Thus, into 2025, Fannie and Freddie remain in conservatorship, 16+ years on, with their future dependent on administrative action or new laws. Their current condition is one of robust profitability and improved risk management, but constrained by the lack of capital freedom and the overhang of government’s senior claims.

Timeline 2008–2025 (Highlights):

2008: FHFA placed GSEs in conservatorship; Treasury PSPA executed (funding commitment up to $445 B, 10% dividend + warrants).

2009–2011: Treasury support used ($189 B drawn by 2012). GSEs delisted from NYSE (now trade OTC). Portfolio reduction and credit reforms begin.

2012: Net Worth Sweep implemented – ending predictable 10% dividend in favor of sweeping all quarterly profits to Treasury.

2013–2016: GSEs turn enormously profitable as housing recovers, but all earnings paid to Treasury. Shareholders sue over NWS (beginning decade-long litigation).

2017–2018: Legislative reform efforts (U.S. Congress) stagnate. Trump officials signal desire to end conservatorship administratively.

2019: FHFA (Calabria) and Treasury agree to allow earnings retention. Fannie/Freddie resume building capital after a decade of zero net worth.

2020: FHFA issues new capital rule (ERCF) mandating ~$280–300 B combined capital. COVID mortgage forbearance programs launch, with GSEs supporting market through interventions.

2021: Supreme Court Collins v. Yellen decision – upholds legality of NWS (no damages for past sweeps) but strikes FHFA director’s insulation (President can fire FHFA head at will). Biden replaces Calabria with Sandra Thompson. Treasury suspends some PSPA restrictions (like limits on certain loan acquisitions).

2022: Sandra Thompson implements minor ERCF tweaks (e.g. removing planned “countercyclical buffer” reduction, effectively keeping capital requirements high). GSEs continue accumulating capital, no major policy shifts.

2023: Court developments (see Legal Overhang) – jury awards shareholders $612 M in NWS damages. Little movement on legislative reform; focus shifts to 2024 election.

2024: GSEs’ retained earnings push net worth near $160 B combined. U.S. presidential campaign brings GSE future back to spotlight (with Republican candidates signaling privatization leanings).

2025: Political regime change – President Donald Trump (re-elected) prioritizes ending the conservatorships. A new FHFA Director, Bill Pulte (confirmed March 2025), rapidly moves to restructure the agencies’ leadership and plans (see Recent Developments). By May 2025, markets anticipate an imminent push to “recap and release”, fueling a speculative surge in GSE equity prices.

In sum, Fannie and Freddie sit at the nexus of public policy and private capital. Their dual role – maximizing shareholder value vs. serving a public mission – has been unresolved since 2008. This backdrop sets the stage for the latest chapter of potential reform, which will determine the fate of common shareholders (who currently own a highly diluted claim on a future recapitalization) and preferred shareholders (who hold contractual rights to dividends that have been suspended since 2008).

Recent Developments (Past 12–18 Months)

Political Reset and New FHFA Leadership: The most consequential recent development is the outcome of the 2024 U.S. elections. President Trump’s return to office in January 2025 fundamentally shifted GSE policy expectations. In March 2025, Trump installed Bill Pulte as the new FHFA Director (after dismissing former Director Thompson). Pulte, a housing investor and vocal critic of GSE bureaucracy, wasted no time initiating an overhaul. Within weeks:

Agency Shake-Up: Pulte placed 35 FHFA employees on administrative leave and forced out several senior executives, including Freddie Mac’s CEO (Mike DeVito). He also reportedly shuttered two divisions of FHFA, cutting ~10% of staff, in an effort to “streamline” the regulator. These actions, made with little warning, caused internal upheaval and drew scrutiny from lawmakers concerned about stability.

Board and Management Changes: FHFA under Pulte overhauled the boards of Fannie and Freddie, installing new members aligned with administration priorities (including, controversially, an official from the Department of Government Efficiency on Fannie Mae’s board). The implication is tighter government oversight of management decisions. Freddie Mac’s CEO was fired in March 2025; interim leadership was put in place pending a search for new CEOs committed to executing the privatization agenda. (Fannie Mae’s CEO as of early 2025, Priscilla Almodovar, has so far remained in her position, but further leadership churn is possible.)

Policy Directives: Via tweets and public statements, Director Pulte signaled intentions to “strip away unnecessary bureaucracy” and reduce GSE operating costs. He also suspended or rolled back certain mission-oriented programs initiated under the prior regime – for example, affordable housing initiatives like Special Purpose Credit Programs were ordered terminated in March 2025. The new FHFA leadership emphasizes refocusing on core business and prepping the GSEs for life outside government control, aligning with a broader Trump administration theme of reducing federal role in housing.

These moves, while dramatic, underscore the administration’s seriousness about GSE reform. However, they have introduced operational risk and uncertainty in the short run (staff morale, potential legal challenges from ousted personnel, etc.). Congressional oversight hearings have been hinted – e.g. Senators sent letters to Director Pulte in March 2025 demanding clarity on his actions and conservatorship plans. The political tension between an executive branch eager to act and legislators worried about mortgage market disruption is a defining feature of the current context.

Administrative Signals: President Trump himself has directly weighed in. On May 22, 2025, he posted on social media that he is giving “very serious consideration” to spinning off Fannie and Freddie as private entities and will decide soon, in consultation with Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, FHFA’s Pulte, and others. This explicit public signal – essentially confirming that privatization is on the near-term agenda – sparked a major rally in GSE securities. Fannie’s OTC stock jumped 33% in a day (to ~$9.94), and Freddie’s 27% (to ~$7.15), reaching their highest levels since 2008. The market is clearly pricing in a significant chance of action.

Treasury Secretary Bessent (a hedge fund veteran) and other Trump officials have echoed that recap and release is a priority. Informally, there is talk of using executive authority to end the conservatorships without new legislation – likely by amending the PSPAs to restructure Treasury’s stake and raising capital from private markets. Key policy proposals being floated include: converting some or all of Treasury’s senior preferred into common equity (or subordinated debt), exercising the warrants and then selling the government’s common shares gradually to investors, and possibly offering current preferred shareholders a deal (conversion to common or cash settlement) to clean up the capital structure. While formal term sheets have not been released, the administration’s public comments have emboldened investors that historic progress may finally be imminent.

Legislative Developments: In contrast to the flurry of administrative activity, Congress has not yet advanced any GSE reform legislation in the past year. The issue remains contentious and, with split party control (assume Republicans hold the House in 2025, Democrats narrowly hold the Senate), significant housing finance bills face steep hurdles. Notably, some Democratic lawmakers have raised alarms about the administration’s unilateral approach – emphasizing concerns that privatization could raise mortgage costs or reduce affordable housing efforts. They argue that Congressional approval should be required for major changes to the GSEs’ status. However, absent a specific bill, this opposition so far has taken the form of oversight (letters, hearings) rather than actionable law. The House Financial Services Committee (now Republican-led) has generally been supportive of reducing government involvement in the GSEs; we may see hearings framing privatization as long-overdue free-market reform. Meanwhile, the Senate Banking Committee (Democratic chair) is likely to scrutinize any administration steps and could introduce messaging legislation to protect affordable housing mandates or even limit FHFA’s authority – but such bills would probably not become law in the near term. In summary, no new laws have been passed; the heavy lifting is being done via executive action under existing authority.

Regulatory & Credit Updates: Over the last 12–18 months, aside from the seismic leadership changes, there have been incremental regulatory developments:

Capital Rules: In late 2022 and into 2023, FHFA made technical adjustments to the ERCF. For instance, it removed the planned “countercyclical adjustment” that would have temporarily lowered capital requirements in periods of rapid house price growth, effectively keeping required capital higher. Under Director Thompson, FHFA maintained a conservative stance on capital, which the new regime may revisit (expect possible future rule changes to ease capital requirements for certain low-risk assets or recognize credit risk transfer more favorably).

Pricing and Credit Policy: FHFA in 2023 implemented changes to the GSEs’ Loan-Level Price Adjustments (LLPAs – fees charged based on borrower credit characteristics). A controversial adjustment in early 2023 slightly increased fees for higher-credit-score borrowers and lowered fees for riskier loans (to promote equity), prompting political backlash. FHFA later rescinded a planned debt-to-income ratio LLPA due to industry pushback. These pricing moves were modest, but they became a talking point about GSE mission vs. safety: the new FHFA leadership has frozen any further such “social policy” pricing tweaks. We anticipate a return to purely risk-based pricing.

Credit Risk Transfer (CRT): Both GSEs ramped up CRT issuance in 2023–2024 as a capital management tool (Freddie transferred credit on $63 B UPB in Q1 2025 alone). FHFA has generally supported CRT, though under Thompson it reduced capital relief credit given for CRT exposures. Pulte’s FHFA may restore more favorable treatment to encourage shedding credit risk to private investors, aligning with a privatization narrative.

New Products/Programs: The GSEs continued initiatives like expanded credit scoring models (moving beyond classic FICO to incorporate newer scores) and Duty-to-Serve affordable housing efforts through 2024. In late 2024, they started rolling out acceptance of alternative credit scores (FICO 10T, VantageScore) and new equity-sharing mortgage pilots. These were mandated by prior FHFA policy. Under Pulte, some of these efforts are paused or under review, but many are in flight and supported by lenders. We may see a slowdown in any new pilots that are not strictly aligned with core business.

Market Conditions: Over the past year, rising mortgage rates (peaking ~7% in late 2024) led to lower refinance volumes but stable purchase mortgage demand. Both GSEs maintained profitability despite reduced new business volume, thanks to strong guarantee fees and stable credit performance. House prices nationally were roughly flat to +3% year-over-year through early 2025, avoiding a severe correction and thus keeping credit losses low. This benign credit environment has helped ease immediate conservatorship concerns (no new Treasury draws needed, etc.). It also sets a favorable stage for raising equity capital (investors are more receptive when loan books are performing well).

In summary, the last 12–18 months transformed the outlook: political winds have shifted decisively towards action. An administration openly committed to ending the status quo is in charge, and early steps have been taken to pave the way (albeit contentiously). No major legislative or negative credit events have impeded this trajectory. The key development to watch now is the expected administrative blueprint for recapitalization – which could emerge via a Treasury/FHFA plan announcement or term sheet in the coming months. Meanwhile, day-to-day GSE operations and financial performance remain solid, even as the institutions brace for potentially the biggest transition in their history.

Legal and Litigation Overhang

For over a decade, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s equity has been clouded by shareholder lawsuits challenging the terms of conservatorship – particularly the 2012 Net Worth Sweep (NWS). While many claims have been resolved (largely in the government’s favor), some legal overhang remains. Here are the major cases and their status:

Collins v. Yellen (Supreme Court 2021): This was a pivotal case by shareholders arguing that FHFA exceeded its authority with the NWS and that FHFA’s structure was unconstitutional. In June 2021, the Supreme Court delivered a split decision. It upheld the NWS (denying relief on the claim that sweeping all profits was illegal under FHFA’s conservator powers) – effectively ending hopes that courts would unwind the NWS or return past dividends. However, the Court found the FHFA Director’s insulation from presidential removal to be unconstitutional (a separation-of-powers issue). The remedy was limited: it allowed the President to remove the FHFA head at will (which had already occurred when President Biden replaced Director Calabria). Crucially, SCOTUS did not invalidate any past actions (Treasury kept the ~$300B in swept dividends). Collins thus eliminated most legal avenues to overturn the PSPA terms. On remand, claims that shareholders might be owed damages for the unconstitutional removal provision have made little headway – it’s challenging to show specific harm from that provision once the NWS itself was deemed within FHFA’s statutory power.

Lamberth Contract Claims (Fairholme class action, D.C. District Court): Shareholders pursued an alternative theory: that the NWS breached the implied covenant of good faith in the stock purchase agreements (essentially a contractual claim, not barred by sovereign immunity). In a landmark jury trial in Washington D.C. (August 2023), jurors sided with shareholders. They found FHFA’s 2012 profit sweep “arbitrarily and unreasonably” violated shareholders’ reasonable expectations, awarding $612.4 million in damages. This sum is to compensate junior preferred and common shareholders for the diminution in value caused by the sweep. In October 2023, Judge Lamberth upheld the verdict and added ~$170 million in prejudgment interest, bringing the total judgment to ~$782 million. This was a rare courtroom win for GSE shareholders. The government (FHFA and Treasury) has appealed the verdict to the D.C. Circuit, where it remains pending as of May 2025. Impact: If the verdict stands through appeals (a process that could extend into 2025–2026), shareholders would receive a cash payout (e.g. class members might recoup a few dollars per share). More broadly, the finding underscored that FHFA’s action “violated the contractual rights” of shareholders, which is a moral victory. However, the remedy is purely financial; it does not unwind the NWS or restore dividend rights going forward. The precedent might deter similarly extreme actions by FHFA in future, but FHFA’s conservatorship powers remain largely intact. This case slightly improves the negotiating leverage of preferred shareholders in any settlement discussions – showing that the government’s conduct wasn’t beyond legal reproach, hence perhaps warranting compromise.

Takings Claims (Court of Federal Claims): Another set of lawsuits (led by hedge funds like Fairholme) argued that the NWS and the ongoing conservatorship effects constituted an unconstitutional taking of private property under the Fifth Amendment, for which compensation is due. These cases proceeded in the Court of Federal Claims. In 2022, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit effectively rejected the takings claims, concluding that shareholders do not have a property right to GSE dividends or to the value of their shares independent of the conservatorship’s terms (partly because the PSPA and HERA gave FHFA broad powers). The Supreme Court declined to review that decision. Thus, takings claims have hit a dead-end, removing what was once a significant legal threat to the government.

Other Litigation: A few miscellaneous cases are on the radar:

Class Action in Delaware (and Virginia) – Shareholders filed in GSE charter states arguing the NWS violated state corporate law (exceeding authority of preferred stock provisions). These were effectively shut down after Collins/SCOTUS and other rulings that federal law (HERA) preempts such claims.

Accounting Fraud Allegations – Earlier suits claimed the government forced excessive loss provisioning in 2008–2011 to justify the conservatorship. Courts have dismissed these as speculative and time-barred.

Preferred Shareholder Contract Claims (pre-2012) – Some claims that suspension of preferred dividends since conservatorship was a breach. FHFA’s position as conservator allows it to suspend dividends, and courts have not contradicted that.

At this stage, the legal overhang is notably lighter than a few years ago. The Supreme Court essentially closed the door on reversing the conservatorship or the PSPA financial arrangements via judiciary. The one material ongoing case is the Lamberth $612M jury award, which, if upheld, results in a one-time payment to shareholders (likely easily absorbed by the GSEs or Treasury). The award is substantial for investors (nearly the current market cap of some junior pref classes) but not life-changing for the GSEs’ balance sheets. It does not force any structural change.

From an equity valuation perspective: earlier speculative hopes that a court might cancel Treasury’s stake or invalidate the government’s 79.9% warrants have not materialized. Instead, what remains is largely a political and administrative question. Investors can no longer pin their thesis on a judicial “bailout.” The path to value realization must come through negotiation or policy (or an unlikely act of Congress), not courtroom victory. The relative win in the contract case may encourage the administration to settle with junior preferred holders rather than continue protracted litigation – a factor possibly in favor of pref share recovery. But importantly, FHFA as conservator still has sweeping power under HERA to act in “best interest” of the GSE or public, which courts have upheld even when it disadvantages shareholders.

One additional legal consideration: Statute of limitations and the mere passage of time. The conservatorship has lasted so long that most legal challenges to its imposition or early actions are time-barred or moot. Conversely, if the current administration moves to end the conservatorship, it will likely seek releases or settlements of any remaining claims to clear the path. We may see, for example, in a recapitalization transaction, an exchange offer to preferred shareholders that is coupled with a legal release of claims.

Bottom Line: The legal sword of Damocles that once hung over the GSEs (the possibility that courts could upend the profit sweep or force a recompense far larger than $612M) has largely been removed. There remains a modest litigation overhang – primarily the outcome of the $612M judgment on appeal – but this is not thesis-changing for equity holders. If anything, the resolution of key cases has clarified that ultimate value will be determined by policy choices, not a deus ex machina from the judiciary. Equity investors should thus focus on political/regulatory developments, treating legal outcomes as secondary and mostly already baked into prices.

Exit Pathways & Scenario Analysis

After 16 years of conservatorship, the potential exit pathways for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac can be grouped into two broad routes: administrative action by the executive branch (FHFA and Treasury) or legislative reform by Congress. We evaluate each, along with likely scenarios, timing, and impacts on the capital stack.

1. Administrative Recap and Release: This is the scenario currently in play under the Trump/Pulte plan. FHFA as conservator has legal authority to end the conservatorship when the GSEs are deemed stable and solvent, and can implement restructuring via amendments to the PSPA with Treasury (no new law needed). The government would use its existing powers to recapitalize and release the GSEs roughly as follows:

Step 1: PSPA Amendment: Treasury and FHFA negotiate a new amendment to remove or revise the profit sweep and other covenants. This could include cancelling the remaining commitment (turning off Treasury’s backstop in exchange for a one-time exercise of warrants or conversion of the senior preferred). More likely, the commitment (currently $256 B unused combined) might be left in place initially to reassure MBS investors, but terms adjusted.

Step 2: Capital Restructuring: Addressing the $340+ B senior preferred liquidation preference is key. Options:

Convert a large portion of the senior preferred into common equity. For example, Treasury could convert enough of its $216 B (Fannie) and $132 B (Freddie) claims such that each GSE’s book equity meets or nears ERCF requirements. This would immediately create an immense number of new common shares owned by Treasury (diluting existing common roughly 5:1, since Treasury would get ~4.6 billion new FNMA shares if fully exercised/converted vs 1.16 billion current).

Alternately, Treasury could write down some of the pref in exchange for other consideration (e.g., an upfront payment from new capital raised or a fee). A full write-off is politically unlikely (optics of a “gift” to shareholders), but a partial reduction might be justified to facilitate private investment.

Maintain part of Treasury stake as debt or preferred in new capital structure – e.g., convert senior pref into a long-term subordinated note, so it’s not equity (for capital ratio purposes) but Treasury still has a claim. This might ease meeting ERCF ratios by removing it from equity.

Step 3: Public Capital Raise: The GSEs likely need additional external equity capital on top of retained earnings to hit required levels quickly. This means one or more secondary offerings/IPO of new common stock to investors. The scale could be on the order of $50–100 B (some estimates even higher) across both enterprises to fill the shortfall. Given market conditions, a staged approach is possible: e.g., an initial raise of ~$20 B (enough to boost capital and demonstrate viability), followed by follow-on offerings over time. The Treasury could coordinate large institutional investors or sovereign wealth funds to take cornerstone stakes. Pricing these offerings will depend on investors’ confidence in a post-conservatorship GSE earnings stream and the resolution of government claims.

Step 4: Warrant Exercise: Treasury exercising the 79.9% warrants is a near certainty in an admin exit – it’s how taxpayers capture upside. Treasury would then hold the vast majority of common shares post-exercise (before any new issuance). One could imagine Treasury exercising and simultaneously selling a portion via the public offering to provide float (similar to how AIG’s recap was handled). The timing is delicate: exercising all at once could crater the stock, so it might be done in tranches or via an agreement to not flood the market.

Step 5: Preferred Stock Settlement: Junior preferreds must be dealt with to have a clean capital structure. The administration could offer to convert preferred shares into common at some ratio or do a cash tender. For example, each $25 par preferred might be converted into common shares worth, say, $20 (an implicit 20% haircut) – current pref investors might accept this, as $20 is ~2× the recent market price. Alternatively, if sufficient new capital is raised, they could redeem preferreds for cash at a negotiated discount. The exact approach will depend on negotiation and avoiding legal disputes – remember, these prefs have contractual rights that could complicate a straight wipeout. A voluntary exchange offer is the likely path.

Step 6: Release and Ongoing Supervision: Once recapitalized (or on a clear path), FHFA would release the GSEs from conservatorship. They would operate as public companies regulated by FHFA (as a normal regulator, not conservator). Expect conditions: e.g., capital restoration plans must be maintained, and perhaps a consent order limiting certain risky activities until fully compliant with ERCF. The Treasury backstop might remain temporarily (for investor confidence), possibly in exchange for an ongoing fee. Eventually, the PSPA could be terminated, fully privatizing the entities.

Decision Tree & Timing: An optimistic timeline might be: 2025: Announce framework and initial PSPA amendment; 2026: execute capital raise and conversions, officially end conservatorship; 2027+: GSEs operate under heightened oversight but as private shareholders-owned entities. However, obstacles (market conditions, political pushback, court challenges by dissenting shareholders) could delay this. If the current administration fails to execute by the 2028 warrant expiry, there’s a risk the process stalls or a new administration reverses course.

Probability and Impact: We gave ~50% probability to this Recap & Release scenario in the Executive Summary as it stands in mid-2025. If achieved, common shareholders’ fate hinges on dilution vs. enterprise valuation. A successful recap could value the combined companies at levels comparable to large financial institutions (perhaps 1.0× tangible book if investors trust the franchise). With full capital, book value could be ~$300 B; if traded at that, Treasury’s portion (80%) would be ~$240 B, leaving ~$60 B for existing common and converted preferred. That outcome would imply multi-bagger returns from today’s market cap (FNMA ~$10 B at $9/share; FMCC ~$4.5 B at $7/share). However, the distribution of that $60 B between current common vs. juniors depends on conversion terms. Common shareholders are likely to see heavy dilution (their percentage cut potentially to single-digits if new money and warrant shares dominate). Still, the absolute value per share could rise if the pie grows enough. Preferred holders in this scenario likely get near-par, as political calculus may favor “making them whole” (since many are retirees, community banks, etc., as often pointed out in lobbying efforts).

2. Legislative Reform: The other pathway is if Congress enacts a comprehensive housing finance reform law. This could either complement the administrative approach or take a very different tack. Historically, legislative proposals have included:

Utility Model Legislation: Convert Fannie and Freddie into regulated utilities with explicitly capped returns and explicit government guarantee on MBS. For example, one blueprint imagined turning them into utilities paying fee to a federal insurance fund, in exchange for an explicit backstop, with regulated pricing and fixed dividend to investors. This could potentially involve chartering them under a new statute, merging into a single entity or two specialized entities (one for single-family, one for multi-family).

Multiple Guarantor System: Some bills suggested phasing out Fannie/Freddie in favor of allowing private companies to issue MBS with a federal guarantee on catastrophic losses (through a platform like Ginnie Mae). That implies winding down the GSEs or breaking them up into smaller guarantors.

Recap with Conditions: Congress could authorize Treasury to sell its stakes and require certain affordable housing mandates or reinsurance mechanisms (e.g., a government reinsurance behind the GSEs’ own capital).

So far in 2025, there is no active bipartisan bill moving. Democrats generally prefer an explicit government guarantee and robust affordable housing support, while conservative Republicans prefer minimizing government credit exposure – a major philosophical divide. The administrative path is proceeding precisely because legislation is seen as unlikely.

If legislation were to arise (perhaps spurred by any market disruption or a compromise in a later Congress), what is the impact on current equity? It depends on how friendly the law is to existing shareholders:

In some utility-style proposals, current common and preferred could be converted into equity of the new utility company, but with dilution or adjusted rights. If lawmakers view current shareholders as having been speculative opportunists, they might wipe out or severely dilute them as a political statement (similar to how Congress treated pre-conservatorship shareholders in rhetoric post-2008). On the other hand, if by then hedge funds and investors have normalized GSE shares, Congress might grandfather them in.

A legislated solution might also address the warrants and senior pref explicitly – e.g., directing Treasury to exercise and sell the stock over time, using proceeds for affordable housing funds, etc.

Legislative reform could take longer (2-3 years even if started) and likely would not happen unless a consensus emerges that administrative tinkering is insufficient or undesirable. Perhaps if a future administration is less keen, Congress might step in to formalize a utility model.

3. Alternative Administrative Scenarios: Beyond the two extremes (full release vs. status quo), there are intermediate administrative possibilities:

Indefinite conservatorship with tweaks: If the current push falters (say markets won’t absorb a big equity issuance), the GSEs could remain in cons., but FHFA/Treasury might make incremental changes to improve investor sentiment – e.g., modestly reduce the senior pref liquidation growth (allow some earnings to count as build-up without increasing gov claim), or even start paying a token dividend to Treasury again (though that would slow capital build). Essentially a holding pattern where the GSEs keep retaining earnings for several more years until capital is naturally sufficient (estimated ~7+ years at current earnings). This delays upside for junior stakeholders and keeps commons highly speculative.

Receivership/Restructuring (“Break the Glass”): In a crisis or if privatization efforts failed drastically, FHFA could theoretically place GSEs into receivership (a more drastic step than conservatorship), which would allow for restructuring debts and equity akin to a bank failure resolution. This is the nightmare scenario for legacy equity: in receivership, common and preferred shares could be canceled or paid pennies on the dollar in liquidation priority (the law (HERA) mandates FHFA as receiver to pay Treasury’s senior pref first, which would wipe out juniors in any insolvency scenario). Receivership was avoided in 2008 due to systemic risk and is very unlikely now absent a severe credit event. It’s a last resort “break glass” option if, say, the housing market crashed and GSEs needed new bailouts – not a base-case scenario.

Merger of Fannie and Freddie: There have been occasional suggestions to merge the two into a single combined entity for efficiency (they already issue Uniform MBS interchangeably). Administratively, a merger during conservatorship could be attempted (with Treasury and FHFA approval). This would simplify eventual exit (one company instead of two) but would raise fairness issues (how to swap FMCC and FNMA shares). Current shareholders might get shares of the merged entity based on relative equity or market cap. This scenario isn’t actively pursued, but it’s out there as a thought. If it happened, likely it’d be neutral to slightly positive for equity (removing redundancy could boost value), but complicated to execute.

Decision Tree:

Trump Admin (2025–2028) – If committed:

Path A: Successful recap & release by ~2026 → Common & preferred realize value (with dilution caveats as above).

Path B: Partial progress only → heading into 2028 election, warrants nearing expiry, either rush a solution or handoff.

If failure (political or market) → Could default to Status Quo or push radical options (e.g., receivership threat to force Congress’s hand, though unlikely).

Post-2028 – If another shift in administration (e.g., Democrat wins 2028):

They may halt or reverse privatization (back to status quo or utility model via Congress). E.g., a Democratic admin might reinstate sweep dividends or heighten affordable housing requirements that conflict with private capital raising, effectively freezing out common equity value again. Preferred might continue legal fights or await a more favorable climate.

Or if Republicans continue beyond 2028, presumably they’d finish any incomplete privatization steps; by then the warrants would have to be exercised (2028 expiry), locking in government ownership share.

Capital Stack Impact by Scenario Recap:

Recap & Release (Admin) – Treasury: likely converts to common and sells over time (taxpayers recoup large windfall). Common: heavily diluted but worth something tangible (a share in a fully private, profitable company). Preferred: converted or paid out near par (restoring their dividend rights in new form). Net effect: Gov stake shrinks over time, private shareholders gain real ownership of GSE earnings, stocks re-rate from speculative to fundamental value basis.

No Reform (Status Quo) – Treasury: maintains senior pref (grows to perhaps ~$400B by decade’s end as earnings accumulate) and does not exercise warrants (maybe extends them). Common: remains effectively a call option on a future political change; intrinsic value stays near zero as all economic value accrues to senior pref (which is not being paid down). Preferred: continue as perpetual non-dividend instruments, trade on hope of future settlement. Capital keeps building but can’t be returned to these investors under PSPA.

Legislative Utility Model – Treasury: might formalize its backstop for a fee or equity stake; could even convert its holdings into a public trust. Common: likely see conversion into utility equity; valuations might be lower (utility P/E ratios) but stable dividend yield possibly. Preferred: could be replaced with new regulated preferred with fixed coupons or cashed out; likely honored given politics, but upside capped.

In evaluating these, investors must consider timing and probability. Our base case leans toward an admin-led recap as the most imminent scenario (before political winds shift again). The decision tree essentially branches on 2024/2025 political outcomes, which we now know. With that branch resolved in favor of action, the next branch point is execution risk – can the plan actually clear the hurdles? We examine those hurdles in the next section (capital and valuation considerations).

In conclusion, the administrative pathway appears open now – it’s arguably the best chance in years to free Fannie and Freddie. But it’s a complex, multi-step process with interdependent pieces (Treasury, FHFA, investors, courts, Congress each playing a role). Scenario analysis suggests that if this path falters, the fallback is not immediately some other grand solution, but rather a prolonged conservatorship (which is bearish for current equity). Conversely, a legislative “big bang” is a lower-probability wildcard that, if it were to happen, could drastically redefine stakeholder outcomes (and likely not in favor of pre-reform equity, given political optics). Thus, monitor closely the execution of the admin recap plan – it is the linchpin of value for FNMA/FMCC at present.

Valuation Deep Dive

Valuing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is unusually complex, given their uncertain future state. We must consider two distinct valuation frameworks: one under the current conservatorship status quo, and one under a recapitalized, released scenario. We also need to account for the unique capital structure elements (Treasury’s senior preferred and warrants, and the junior preferred overhang). Below, we conduct a sum-of-the-parts and scenario-driven analysis.

Status Quo (Going Concern in Conservatorship): In the indefinite conservatorship scenario, common shareholders have no claim on earnings – all profits simply accumulate as retained equity that props up the enterprise (and increases Treasury’s pref claim). In theory, if this continued until capital requirements are met (~$328 B needed, with ~$147 B already available), by around 2030 the GSEs might be fully capitalized. At that point, absent reform, what happens? FHFA could begin allowing dividends or release them anyway. But if we assume pure status quo indefinitely, common equity never sees a dividend or buyback, and on any liquidation Treasury’s $340B+ senior pref takes all value first. Essentially, the intrinsic value of common in strict status quo is near $0 – it’s only worth the option that someday the rules change. Markets recognize this, which is why before recent reform hopes, FNMA/FMCC stock traded under $2, a tiny fraction of book value.

One could attempt a DCF of status quo: The GSEs would continue earning ~$20–25 B/year combined, growing book equity (which belongs to Treasury’s claim) until maybe 2030 when required capital is reached. After that, if nothing changes, they might start paying a 10% dividend to Treasury on the growing pref (or some revised deal). From the perspective of junior shareholders, the cash flow is zero in all those years. Only if at some distant point FHFA decides to end the sweep would cash flow start. The net present value of such a distant hypothetical is deeply discounted. This explains why, absent concrete reform prospects, the commons trade like perpetual call options. Preferred shares under status quo similarly accumulate unpaid dividends (in theory, though non-cumulative, they just sit in arrears conceptually) – they too get nothing until a catalyzing event. However, preferred have a stronger eventual claim (they’d rank ahead of common if the company were released or wound down). This is why preferreds have tended to trade at some portion of par (reflecting an expected recovery fraction). Without reform, they could remain unredeemed and non-income-generating indefinitely, but investors might eventually get liquidation preference if the GSEs ever exit or are liquidated. So status quo valuation for prefs might be the probability-weighted present value of a par recovery in some future scenario, plus maybe small chance of receivership scrap value.

In summary, status quo valuations are driven entirely by speculative probability of change, not fundamentals. By fundamentals alone, current common is essentially a claim behind a $340B government stake – essentially worthless. Preferreds at least have contractual par value that in any non-zero outcome must be dealt with, so they have a floor under positive scenarios. This asymmetry is why preferreds trade higher relative to potential payout than common (lower risk, though still high risk). If one believed conservatorship would never ever end, the rational value of both common and junior pref would asymptotically approach zero (since any residual value in 2080 or beyond is negligible today).

Recap/Release (Fundamental Value Analysis): In a scenario where GSEs are freed and recapitalized, we can value them more like normal financial institutions – based on earnings power, growth, and required capital structure. Key components:

Earnings Power: Both GSEs have demonstrated stable earning capacity. For 2024, Fannie Mae earned $17.0 B, Freddie Mac around $9–10 B. Combined, that’s ~$26–27 B in annual net income. This reflects guaranty fee revenues on a ~$7.7 T book, credit losses near historic lows, and some interest income from portfolios. Going forward, growth in earnings will depend on the mortgage market (new guarantee volumes, fee rates) and credit conditions (loss provisioning). The GSEs’ earnings are partly like an insurance float business (g-fees) and partly spread business (investing their capital and some retained portfolios). Under a fully private model, they might target a return on equity (ROE) around 10–12% given their quasi-utility status. We should consider that if they hold a full 4% capital on $7.7 T assets, that’s ~$308 B capital; earning $25 B on that is only ~8% ROE. Indeed, analysts have noted the ERCF capital requirements seem excessive, producing pro forma ROEs in high single digits. This could pressure them to either raise guaranty fees (risking mortgage rates) or accept lower returns. A possible outcome is FHFA revises capital down somewhat or the market prices the stock at less than book if ROE is subpar.

Valuation Multiples: Pre-2008, Fannie and Freddie traded around 10–12× earnings or about 1.5× book value, reflecting high ROEs (~20%+) then. Post-release, with more capital and less growth, they might trade closer to book value or even a discount if ROE is <10%. Comparable financials: large banks trade ~1.0× book for ~10% ROE; mortgage insurers trade at ~1× book for mid-teens ROE; mortgage REITs trade below book when ROEs are mid-single-digit. If GSEs are utilities with 8–10% ROE, 0.8–1.0× book might be reasonable. Conversely, if they can optimize and get ROE to >10%, maybe slightly above book.

Sum-of-the-Parts: Fannie and Freddie’s businesses can be segmented into:

Guarantee Business: A stable fee income stream somewhat like an insurance company. This could be valued by a yield or multiple of earnings. The present g-fee revenues (~$7.1 B for Fannie in Q1 annualized, ~$5.9 B for Freddie) after credit costs translate into the net incomes above. If we believe $25 B/year sustainable combined, at a say 10× multiple, enterprise value ~ $250 B.

Retained Mortgage Portfolio: Each GSE still has a retained portfolio (capped by PSPA, but in a free scenario they might manage a modest portfolio for liquidity/investment). Currently, net interest income from portfolios and other investments is significant (e.g., Freddie had $5.1 B NII in Q1 2025). As rates rise and fall, this component can produce gains or losses. But it’s mostly a supporting role now; could be valued near book value of those assets or on NII yield.

Deferred Tax Assets (DTA): After huge losses in 2008-2011, GSEs have DTAs that they reinstated in 2013. Fannie’s DTA was ~$50 B then; much has been utilized, but a sizeable DTA remains (which is part of their $98 B net worth). In valuation, DTA is an asset that reduces future taxes – effectively increasing earnings over time. Any valuation should account for the fact that reported earnings benefit from using DTA (no cash taxes until it’s exhausted). A buyer might value the DTA at somewhat less than face (time value).

Credit Risk Transfer (CRT) impact: The GSEs offload some credit risk via CRT deals. This reduces potential losses (and reduces required capital marginally) but also costs them in interest/hedge expense (reflected in earnings). If fully private, they might expand CRT to optimize capital (since CRT can substitute for equity for risk coverage). That can enhance ROE if done efficiently. For valuation, heavy CRT use could allow a smaller required equity base for the same risk – effectively boosting ROE or freeing capital to return to shareholders, which would justify higher valuations. Current FHFA rule limits some CRT capital benefit, which could be loosened.

Modeling a Recap Scenario: Let’s illustrate a potential steady-state for Fannie Mae post-release:

Suppose required Tier 1 capital is around 10% of risk-weighted assets (or ~3.5% of total assets). For Fannie, with ~$4.5 T assets (adjusted), that’s roughly $160 B needed (aligns with ERCF). If Fannie has ~$100 B today, it needs +$60 B. That could come from, say, converting $40 B of Treasury pref to common and issuing $20 B new shares.

Post-recap, Fannie might have ~5.7 B shares (existing 1.16 B + 4.6 B from warrant + maybe ~0.5 B from new issue if priced around $40). If fully valued at book, market cap might be ~$160 B (if book = capital = $160 B). That’s ~$28/share. Existing common (20% of the company pre-new issue) ends up owning perhaps ~15% after new issue, so their portion would be ~$24 B, or effectively $20/share for current stock. That’s one optimistic scenario (assuming 1.0× book valuation).

If valuation is only 0.8× book, that share might be more like $16. If required new issuance or conversion terms are worse for existing holders (e.g., issuing more shares at lower prices), their slice shrinks.

Preferreds in such scenario: if converted at par, $33 B par would take maybe another chunk of shares (diluting common further). Likely they’d structure it so preferred get, say, $25 B in value (approx 75% of par) to balance interests, which still significantly dilutes. Each variable in this equation changes common’s outcome.

This exercise shows that under plausible assumptions, current common could be worth several times its trading price if recap occurs and the market values the new GSE equity reasonably. But it’s highly sensitive to dilution factors and valuation multiples.

Sensitivity Factors:

Guaranty Fee Changes: Small changes in average charged g-fees can have big impacts. Currently ~50 bps on single-family. If post-release the GSEs raise g-fees (to earn higher ROE on higher capital), they could increase earnings – but this could also contract their volume if it pushes mortgage rates up. There’s a policy tug-of-war here between safety (higher fees, more capital) and affordability.

Interest Rates: Rapid rate swings affect prepayments and the value of mortgage servicing rights, etc. Higher rates in 2022–2023 reduced refi volumes but widened net interest margins on portfolio holdings for a time. The GSEs’ earnings were actually resilient with 30-year mortgage ~6.5%. In a falling rate environment (if 2025–2026 see lower rates), new business might surge (boosting fee income) but they could face negative mark-to-market on their derivatives and credit risk transfers. Generally, moderate rate moves are fine; extreme moves can cause one-time hits (e.g., large hedge losses or credit reserve builds).

Credit Losses / Home Prices: The biggest fundamental risk is a housing downturn. With average LTV ~50% on Fannie’s book and FICO ~753, credit quality is high. Stress tests show the GSEs could withstand a significant home price drop with current capital. However, if home prices fell 20% and defaults spiked, they might incur tens of billions in provisioning. This would dent their capital build and perhaps require raising even more capital in a recap scenario. Conversely, continued home price appreciation or low defaults (as currently) means they’ll enjoy low credit losses (Q1 2025 credit-related expense was actually a benefit for Fannie due to releases of reserves with improving forecasts). So macro conditions can swing annual earnings by several $B via credit costs.

Capital Requirements Changes: A critical sensitivity: if FHFA/Pulte decide to lower the ERCF requirements (e.g., drop the capital buffers, or reduce risk weightings for low-LTV loans, etc.), the needed capital could be, say, $50 B less. That directly increases ROE and reduces dilution needed. There is speculation that current requirements (which some say are “far in excess of what is justified by actual losses”) might be moderated. Each 0.5% of assets less in required capital is ~$20–25 B less equity needed, which could boost valuation for existing shareholders.

Treasury Warrant Treatment: By law/contract, these expire in 2028. If for some reason Treasury chose not to exercise fully (say it left some portion unexercised as a concession), the value remaining would accrue to common. This is unlikely – Reuters reported a market strategist’s view that the government could net >$250 B by listing the GSEs, which clearly assumes full warrant exercise – but it’s a sensitivity: if warrants were reduced or canceled, current common would skyrocket. However, such a giveaway to shareholders is politically radioactive (it would mean handing tens of billions to hedge funds), so we assume full dilution from warrants in any realistic scenario.

Preferred Overhang Resolution: The cost of taking care of preferreds (paying par vs a discount) affects common value. If they insist on par ($33 B outflow or equivalent in shares), that’s more dilution to common. If they accept $20 B, that saves $13 B for common. This may come down to legal leverage and negotiation. The jury verdict discussed earlier gives preferred holders some leverage to ask for better terms (since they proved NWS was a breach, implying government might prefer to appease them). We suspect a middle-ground outcome (e.g., ~75% of par equivalent).

Tax Rate & DTA: A final nuance – corporate tax changes could impact earnings (the GSEs pay the standard 21% federal rate now). Any increase in tax rate would reduce net income (and conversely, lower taxes would boost it). The DTA on books would adjust accordingly. Keep an eye on fiscal policy, though currently no major changes are expected in immediate term.

Market Valuation Snapshot: The market’s implied expectations can be gleaned by comparing trading prices to notional values. For instance, at ~$10/share, Fannie’s common market cap is ~$11.5 B vs a book value (ignoring Treasury pref) of ~$98 B. That’s ~0.12× book – extremely low, but rational given ~80% dilution ahead (after which that 0.12× could equate to ~0.6× on a pro forma basis). Preferreds around $10 are at 40% of par, suggesting maybe a ~40% chance of full par or 80% chance of ~50% recovery, etc. These prices have risen dramatically from a year ago (when common was ~$1–2, prefs ~$3–5), reflecting that investors assign a much higher probability to recapitalization now. In effect, the market might be saying there’s roughly a 50% chance of a favorable recap within a few years (hence common up ~5×). This aligns with our subjective probability assessment.

DCF/Intrinsic Approach Post-Release: We can do a simplified DCF for post-release equity. Assume by 2026 the GSEs have, say, $250 B combined tangible equity. Suppose they can pay out dividends at a 40% payout ratio and grow the book ~5% a year (via retained earnings and modest asset growth). If earnings on that capital are 10% ROE = $25 B, dividends ~ $10 B (to new shareholders, including Treasury while it holds stock). If cost of equity ~12%, the equity’s value as a perpetuity growing 5% would be: $25B – $10B reinvested = $15B free cash, growing 5%, so roughly $15B/(12%-5%) = $214 B equity value. That’s in the ballpark of the capital itself (so ~0.85× book). Different assumptions will change this (if ROE ends up 12%, value would be higher, etc.). But it shows that one can fundamentally justify valuations in the few-hundred-billion range, which makes current sub-$20B combined market cap look very low if one believes that fundamental state will be achieved. Of course, the timeframe and risk to get there justify a huge discount.

Bottom Line on Valuation: We effectively have a binary distribution of outcomes rather than a single intrinsic value. The upside case (recap/release) could see common stock settle at a fundamentally supported level many times the current price (even after dilution, possibly in the high teens or higher per share, vs $7–10 now, if all goes well). The downside case (no reform or adverse reform) could see common nearly worthless or heavily diluted in a way that current price is too high. This asymmetry is why the stocks are volatile and attract speculative interest.

From a common vs preferred perspective: Preferred shares have less upside (they cap at par $25 plus resumption of maybe a ~5-8% yield dividend if reinstated), but also perhaps less downside (in most scenarios short of catastrophic receivership, they should be paid something if the companies are re-privatized or wound down by law). They are akin to a high-yield distressed debt bet on eventual settlement. The common is more like an equity option on political outcomes – in a bull scenario it could exceed preferred percentage gains significantly (e.g., if common went from $10 to $30 that’s +200%, while preferred from $10 to $25 is +150%), but in a bear scenario, preferred might retain some minimal value while common could go to ~$0.

Resolution of Treasury Stake: For valuation, it is also critical to consider Treasury’s ongoing role. Will the government demand some ongoing economics even after release? Possibly:

They could charge a quarterly commitment fee (a PSPA covenant that’s been waived each year, but could be activated upon release). This fee might skim some of the GSEs’ earnings to compensate for the implicit guarantee. In earlier talks, a fee of 10 bps on the guarantee book was floated. On $7.7 T, that’d be $7.7 B/yr paid to Treasury – which would materially reduce earnings available to shareholders. However, if fully private, the guarantee might no longer exist officially. But political reality might impose a fee for any continued backing.

Treasury could also retain some senior preferred instead of converting it all, meaning it continues to have a preferred dividend that must be paid before common dividends. Ideally, the recap plan removes this overhang entirely, but if not, that piece would need valuation as a perpetual gov claim.

Given these uncertainties, any DCF or SOTP modeling must account for potential government charges, higher capital, and possibly lower growth (post-release GSEs might not grow their book rapidly, as they might be constrained by capital or charter limits – e.g., multifamily volume caps, which FHFA already sets).

In conclusion, our valuation analysis underscores two key points:

Enormous gap between status quo value and release value: This gap is essentially the “reform premium.” Right now, markets are pricing in a significant chance of reform, but not a certainty – hence prices are elevated from pure option-value levels but still far below fully privatized intrinsic values.

Dilution and capital are the swing factors: The ultimate share of that intrinsic value accruing to current stakeholders depends on how the recap is done. A shareholder-friendly plan might minimize new issuance and perhaps negotiate the government stake down slightly; a harsher plan could leave current common with only a sliver of the pie. This uncertainty is why even pro-reform investors often favor preferred (more straightforward claim on par) or maintain moderate position sizes in common due to binary risk.

For modeling detail-oriented investors, a sensible approach is to assign probabilities to scenarios, model each scenario’s per-share outcome, and take an expected value. By our analysis, that expected value appears to be somewhat higher than current trading (justifying some investment), but the distribution is extremely wide and sensitive to political events – meaning a classic high-risk/high-reward profile.

Market Comps & Sentiment

Market Comparables: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, in conservatorship, are sui generis – no other financial institutions have their exact profile. However, to gauge potential valuation and investor sentiment, we can compare them to a few groups:

Large U.S. Banks: Mega-banks like JPMorgan or Bank of America operate with ~10–12% capital ratios and earn ~12–15% ROEs. They trade around 1.2× book value and ~10× earnings. If post-release GSEs were valued similarly, given (likely) slightly lower ROEs (due to higher required capital and a narrower business scope), one might expect ~0.8–1.0× book as noted. Pre-2008, the GSEs were highly leveraged but had an implicit guarantee, so they traded richer (Fannie’s P/B was >2× at times, P/E ~8–10× because of high leverage-driven EPS). Those days are gone; the new GSEs would look more like large, low-risk banks.

Mortgage Insurers and REITs: Private mortgage insurers (PMIs) like MGIC or Radian take housing credit risk (though only on high-LTV portions). They trade around 6–8× earnings and often <1× book, partly due to cyclicality of housing and less government backing. The GSEs have more diversified portfolios and a quasi-government aura, so arguably they should trade at less of a discount than PMIs. Mortgage REITs (like Annaly, AGNC) invest in MBS and often trade at 0.8–0.9× book with double-digit dividend yields, reflecting the volatility of their leveraged portfolios. The GSEs’ guaranty business is more stable and utility-like, so one would think a higher multiple is warranted than MREITs. If turned loose with consistent earnings and possibly dividends, Fannie/Freddie might attract yield-oriented investors similarly to utility stocks (perhaps eventually paying modest dividends akin to a 3-4% yield).

Insurance and Guarantee Businesses: One can analogize the GSE guarantee to an insurance model. Financial guaranty insurers (like pre-2008 MBIA, Ambac) insured MBS and traded on the assumption of low loss probability – before they collapsed in 2008. The GSEs differ in having much larger scale and federal oversight. Perhaps a better comp is the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs) – cooperatively owned, thinly capitalized government-sponsored liquidity providers. They are not publicly traded, but they exemplify a utility model (paying just enough dividend to members to keep going). If Fannie/Freddie ended up as something akin to a member-owned utility, their equity might effectively be like a bond substitute (low return, low risk).

International Parallels: There aren’t many. Some countries have national housing finance agencies (often government-owned). Ginnie Mae (in the U.S.) is a government corporation, not comparable for equity. The closest might be Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp (CMHC) – fully government – or China’s housing banks (state-run). These don’t offer market comps but underscore how unusual a partially privatized-but-backed model is.

Current Market Sentiment: Sentiment around FNMA/FMCC is highly speculative and headline-driven:

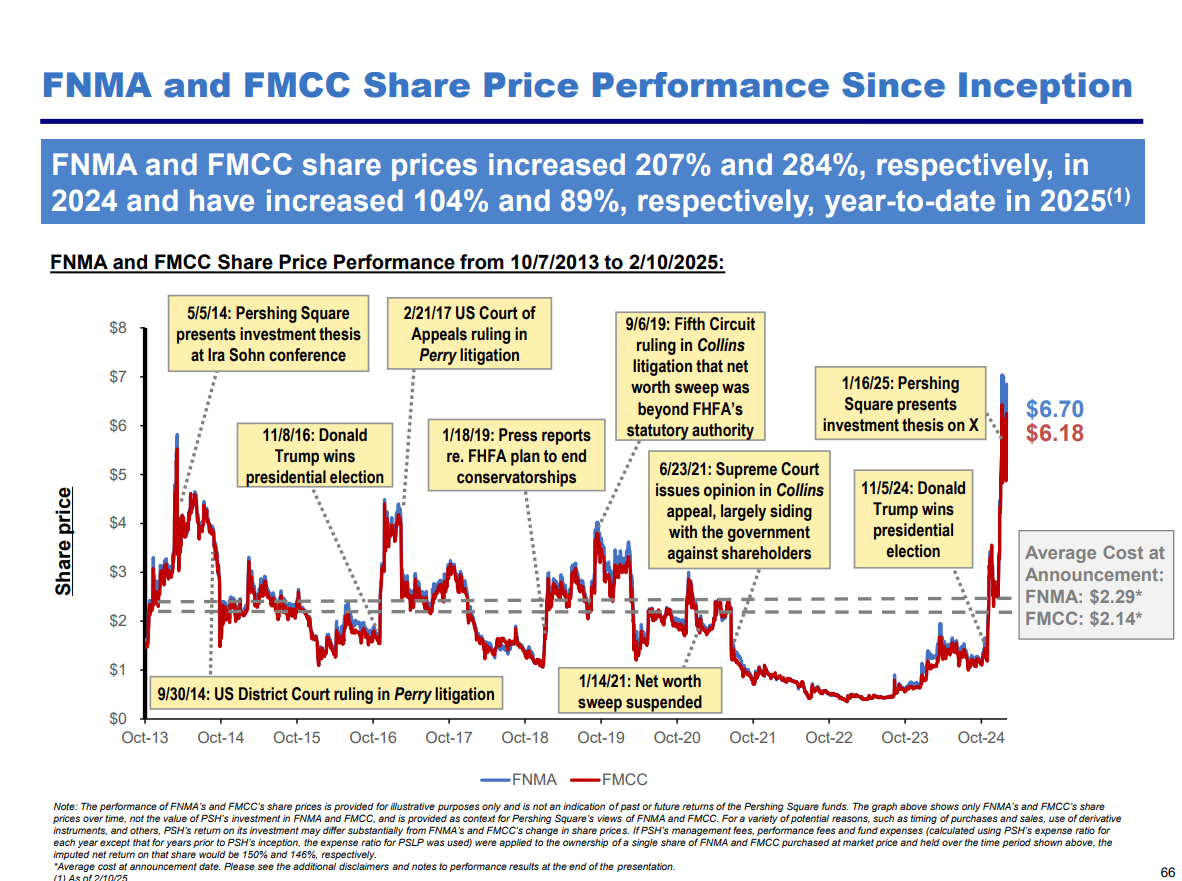

Over the last six months (late 2024 to May 2025), common shares have risen several hundred percent (e.g., up ~325% over six months for FMCC as of early May). This rally was fueled by investor positioning ahead of the election and then actual policy signals. It suggests a mix of retail and hedge fund money speculating on policy outcomes. The stocks are prone to sudden spikes on news (e.g., Trump’s spin-off comment, or Ackman’s public statements) and equally sudden collapses on setbacks (e.g., the June 2021 SCOTUS decision saw shares plunge ~30% in a day).

Short Interest: Data on short interest is limited on OTC stocks, but historically short interest has been relatively low as a percentage of float – partly because borrow is not always readily available, and also because these stocks already trade at low absolute prices (making shorting less attractive relative to upside risk on news). That said, some hedge funds have been known to short common as a hedge against long preferred positions (i.e., betting that if no reform occurs, common goes to zero while preferred might still have some value). If reform looked likely, those hedges could be unwound, contributing to rallies.

Volume & Liquidity: FNMA and FMCC remain OTC/Pink Sheet listed, which limits institutional ownership (many funds can’t hold penny stocks or OTC). However, volume has been significant on news days – for example, tens of millions of shares might trade after a major announcement. Liquidity can evaporate during quiet periods, leading to price drift. If relisted on NYSE/Nasdaq post-release, one could see a broader investor base (index funds, etc.) which could support higher valuations more reflective of fundamentals.

Technical Positioning: There is a contingent of retail investors very dedicated to these stocks (e.g., active on forums like Reddit’s r/FNMA_FMCC_Exit). They often treat the stocks with almost meme-like enthusiasm when news is favorable, talking about multi-bagger potential, referencing high target prices if warrants were canceled, etc.. This can create self-reinforcing spikes. On the flip side, if momentum shifts or if there’s disappointment (say, a reform delay), momentum traders could exit en masse, leading to sharp drops. In essence, volatility is high – 2025 year-to-date, FNMA’s 52-week trading range is roughly $0.50 to $10, illustrating that sentiment swings by an order of magnitude.

Analyst Coverage: Due to their unusual status, Fannie and Freddie have minimal Wall Street equity analyst coverage. They are not included in major indices and not followed like normal companies. Most analysis comes from specialized research boutiques or investor letters (e.g., Pershing Square releases presentations on them). Thus, price discovery is more influenced by those prominent voices and legal/regulatory news than by quarterly earnings beats or misses. The Q1 2025 results, for instance, showed solid profits but that alone didn’t move the stock much; policy news did.

P/B and ROE Snapshot: If we artificially calculate current P/B based on tangible common equity excluding Treasury:

Fannie’s common equity (if one subtracts the senior pref) is actually negative (because Treasury’s $120.8 B original pref counts in equity). But using “net worth” as a proxy (which is essentially total equity including Treasury), P/B is ~0.1× at current prices. That’s meaningless in normal contexts, but reflective of the government claim.

ROE for 2024 was enormous if calculated on the sliver of nominal common equity (because common equity book was near zero). A more relevant metric: return on total capital (including Treasury’s stake) – roughly $26 B combined earnings on ~$300 B total capital (incl. pref) = ~8.7% return on that capital. This is basically the ROE a fully capitalized GSE might have, which again supports the notion that at full capital the valuation would be more middling (not high growth).

Mortgage Market Backdrop: A factor affecting sentiment is the broader housing finance environment. In 2022–2023, rising interest rates and Federal Reserve tightening reduced mortgage origination volumes drastically from the 2020 refi boom. Typically, lower volumes might hurt GSEs’ near-term revenue growth (less new loans to guarantee). However, both companies maintained earnings by increasing average guaranty fees and because their back book of business continues to generate income. Now, with the possibility of interest rates stabilizing or falling by 2025–2026 (as some forecasts suggest due to a potential economic slowdown), investors might anticipate a tailwind of higher originations (especially if rates drop, triggering a refinance wave). Fannie’s economists even forecast additional home sales and originations growth in 2025/26. That could boost earnings and perhaps make raising capital easier (a growth story is more attractive). This macro optimism can feed into sentiment – if investors think a recapitalized Fannie/Freddie will also benefit from a cyclical upswing, they may assign richer multiples.

Bottom Line Sentiment: As of now, the sentiment is speculative but optimistic. The stock prices imply considerable hope for a favorable outcome, but not certainty (they are not trading anywhere near full book value yet). It’s a trader’s market, largely event-driven. For long-term value investors, these waters are tricky to navigate; one has to have a view on politics as much as on P/E ratios. The technical dynamics (OTC listing, retail fanbase, hedge fund positioning) mean that volatility will remain extreme. For instance, if any signal emerges that the privatization might be delayed (say, an official comment pushing timeline to 2027), one could see a large pullback. Conversely, a concrete step (like an announced agreement in principle between Treasury and a group of investors) could send shares surging again.

In comparing to comps, the takeaway is that if/when Fannie and Freddie become “normal” financial stocks, they likely won’t command premium growth multiples given their quasi-utility role, but they could be valued similarly to solid, low-risk financials (around book value, mid-single-digit yields). The journey to that normalcy, however, is what current investors are trying to bridge – and that journey’s outcome remains uncertain, keeping sentiment in a state of flux.

Stakeholder and Ownership Map

Understanding who holds Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac securities – and their motivations – is key, as these stakeholders influence litigation, lobbying, and even the execution of a recapitalization.

Common Shareholders: The common equity is widely held among hedge funds, specialized investors, and retail traders, since traditional institutional ownership is low (due to OTC listing and speculative nature). Notable holders and figures include:

Pershing Square (Bill Ackman): Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital is one of the largest holders of Fannie/Freddie common. Reuters reported Pershing holds about 10% of Fannie Mae’s common shares – roughly ~115 million shares – making Ackman a key stakeholder. He has been invested since 2013/2014 and has publicly advocated for recapitalization plans (Pershing released a “The Art of the Deal” presentation in Jan 2025 outlining a path to privatization). Ackman is viewed as an ally of the Trump admin on this issue (ironically, he wasn’t politically aligned with Trump historically, but here interests coincide). If recap happens, Pershing stands to gain massively. Ackman’s influence: he can mobilize media attention, and he has engaged with policymakers (he met with Trump officials in 2017, etc.). He also likely would participate in any new capital raise (Pershing could invest additional funds if needed).

Retail Investors: There is a strong retail presence – as evidenced by active forums and the meme-stock-like moves. Many small investors hold FNMA/FMCC hoping for the “big score.” Some have held since pre-2008 (legacy holders who saw their value nearly wiped out), while others came in post-2012 as part of the “Fairholme/Ackman trade.” The Investors Unite group, established by shareholder activists, once represented many of these individuals in lobbying efforts.

Other Hedge Funds: In the early 2010s, a number of hedge funds piled into GSE equity (both common and prefs): Bruce Berkowitz’s Fairholme Funds, Richard Perry (Perry Capital), John Paulson (Paulson & Co.), Carl Icahn, etc. Some have since exited or wound down. Fairholme (Berkowitz) was a leading preferred holder and litigant; as of a few years ago, Fairholme still held large positions in Fannie/Freddie prefs (Fannie’s ~$2B par held at one point). Berkowitz’s fund has shrunk significantly, but he appeared vindicated by the Lamberth legal victory (Boies Schiller, his lawyers, touted the win). It’s unclear how much Fairholme holds today, but likely still significant preferred stakes.

John Paulson – His hedge fund was involved early (he made large purchases around 2013). He was rumored as a possible beneficiary in Trump’s plans (the Reddit comment even mentioned him as a potential Treasury Secretary pick with large pref holdings, though in reality Trump chose Bessent). Paulson’s current holdings aren’t public, but he’s probably still exposed via preferreds.

Other Funds: Smaller value funds or family offices may hold positions. Notably, some community banks and insurance companies held Fannie/Freddie preferreds pre-2008 for income; many of those got stuck holding them after dividends stopped. Some may still hold and have lobbied for resolution (for example, railroad retirement fund or teacher pension funds that had small slices).

Arbitrageurs: Given the multiple classes of preferred (each trading at slightly different prices), some investors trade the relative values expecting equal treatment at the end (a convergence trade). Also, some might be long preferred/short common or vice-versa depending on outlook (long pref as safer, short common as overpriced optionality, etc., or opposite if one expects common to get political favoritism).

The U.S. Government: The biggest stakeholder is of course the U.S. Treasury (and by extension the taxpayer). Treasury’s senior preferred stock (liquidation pref ~$348B) and warrants (79.9%) make it the economic owner of most GSE value under any scenario. However, Treasury’s goal is not to maximize profit at all costs; it has policy objectives. Over the years, Treasury’s position (under different Secretaries) has varied: some wanted to use GSE profits for affordable housing or deficit reduction, others (like Mnuchin in 2017–2020) wanted to release them responsibly. Currently, with a Trump-appointed Treasury Secretary (Scott Bessent), the government’s stake will likely be used in a way that aligns with privatization but also yields a politically sellable benefit to taxpayers – hence the talk of a >$250B “windfall” if IPO’d. Treasury will be a key negotiator with shareholders if any deals (like converting preferred or exercising warrants) happen.